Cohesion Policy scenarios

June 2022

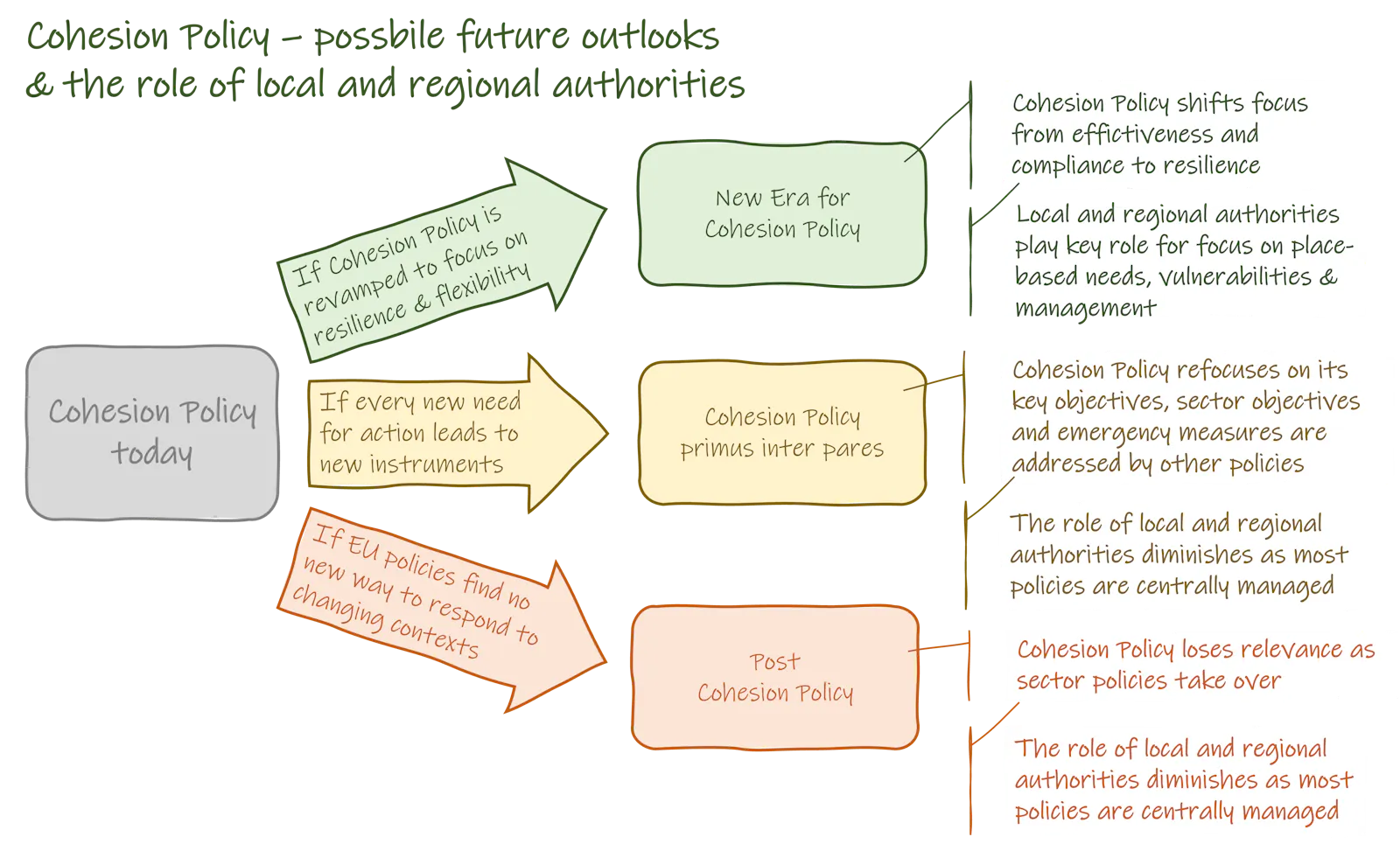

What is the future for Cohesion Policy in a more resilient Europe? European policy making can respond very differently to the need for more resilience. Depending on the overall response, the role of Cohesion Policy and the involvement of local and regional authorities will vary.

Three radically different policy scenarios can depict this (see figure):

The first focuses on a new era for Cohesion Policy. A shift towards resilience and flexibility allows Cohesion Policy to become the main instrument to increase resilience and react to changing contexts or new crises. Instead of developing new policy responses to new policy needs, EU policy making benefits from the experience and virtues of place-based management for Cohesion Policy.

The second scenario focuses on a return of Cohesion Policy to its primary cohesion objectives. Increasingly other objectives for innovation, energy, climate change, etc. are addressed by growing sector policy instruments. New needs, including responses to new crises, are addressed by new policy initiatives.

The third scenario focuses on changing policy needs in a changing world. Here, Cohesion Policy is not adaptive enough to support the need for a more resilient Europe. Subsequently other policy instruments which are more agile, grow and take over. In the long-run this leads to a diminishing importance and finally the phasing out of Cohesion Policy. New policy instruments dominate as they are better suited to the new times.

A New Era for Cohesion Policy

Resilience does not mean a ‘return to equilibrium’, as there is no true equilibrium. It means a constant need to find ‘new’ equilibriums balancing stability and flexibility. This requires the capacity to react and think about alternatives and new scenarios and how to achieve them.

To better respond to the needs of a changing world and support resilience so cohesion objectives are achieved, Cohesion Policy is considerably revamped.

To read this post you'll need to become a member. Members help us fund our work to ensure we can stick around long-term.

See our plans (Opens in a new window)

Already a member? Log in (Opens in a new window)