Dear reader,

You haven’t heard from us in a while, but we continue to work on Alec Riley’s Egypt diary. In the meantime, here is an article we wrote for Digger, the quarterly magazine of Families and Friends of the First AIF (FFFAIF). The society was founded by Australian historian and author John Laffin.

Sorry, you two Australian Mums

The authors have recently brought to publication the Gallipoli diary of Alec Riley, a British Army signaller with the 42nd (East Lancashire) Division at Helles. Riley saw more of the southern battlefield than most as he was attached to six different battalions during his five months at Gallipoli. He kept detailed notes whilst on the peninsula and wrote them up soon after. The resulting account (Gallipoli Diary 1915, Little Gully Publishing, 2021) is a valuable resource for those interested in the fighting at the Dardanelles and the experience of the ordinary soldier.

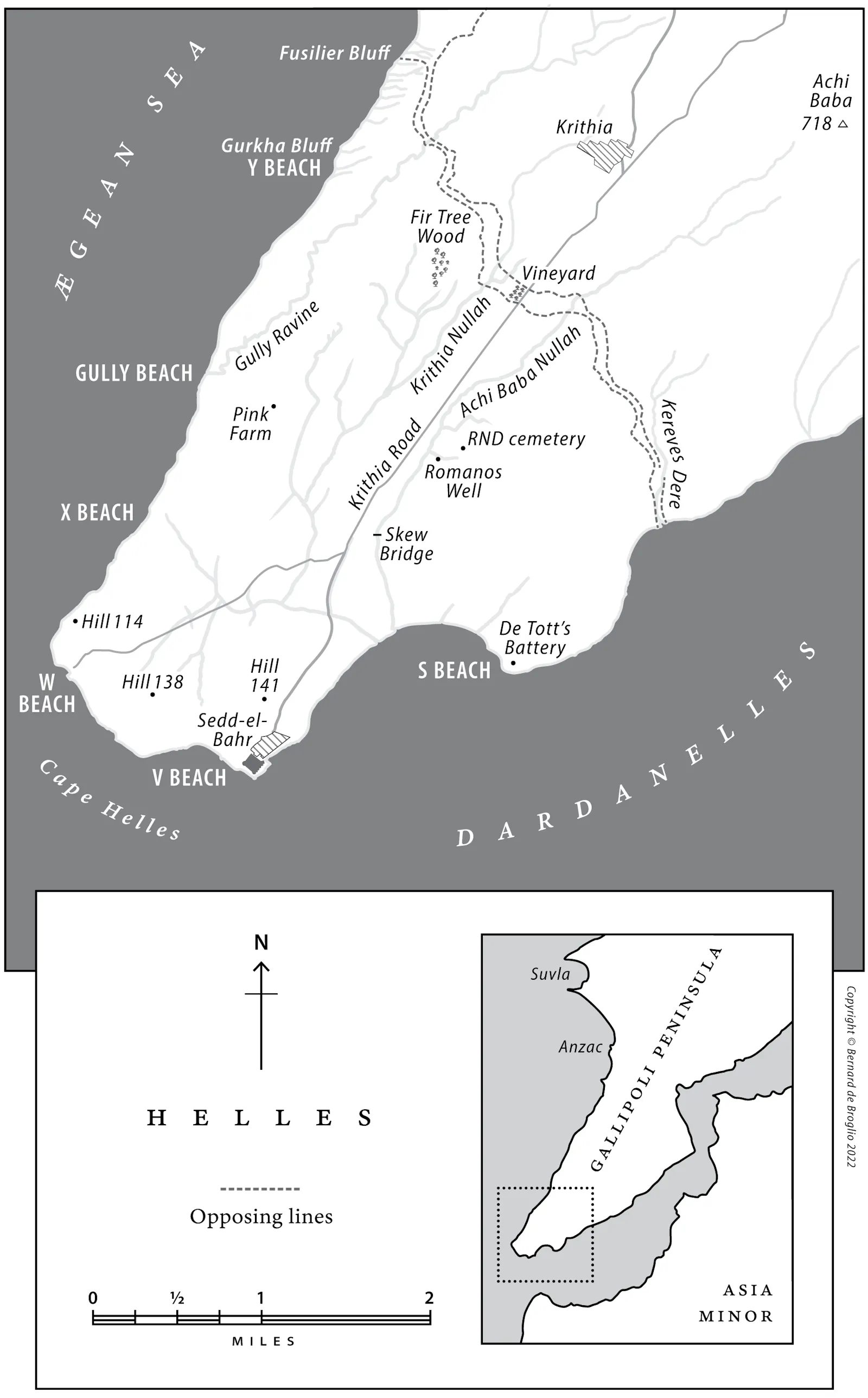

In mid-June 1915, 2nd Corporal Alec Riley was assigned to the 126th (East Lancashire) Brigade. His ‘signal office’ was in the front-line between the Vineyard and the bifurcation of Krithia Nullah into its east and west branches. ‘The trench floor,’ says Riley, ‘was full of maggots from the dead.’ The ground had been taken from the Turk some 10 days earlier, on 4 June, by the 42nd Division. The battalions, whose men were drawn from cities like Bury, Blackburn, Burnley, Manchester, Salford, Oldham and Wigan, suffered terrible casualties in what became known as the Third Battle of Krithia.

Amongst the guns of the British and French corps at Helles were Australian artillery units diverted from Anzac. These were the 1st, 2nd and 3rd batteries of the NSW-raised 1st Field Artillery Brigade (FAB) and 6th Battery, 2nd FAB.[ (Opens in a new window)1]

For Tuesday 15 June 1915, Alec Riley records that:

‘An Australian was killed in the firing-line that afternoon and his body, covered with a blanket, was taken down on a stretcher.’

We believe that unfortunate Anzac to be Gunner 3513 Stanley Pearson of Headquarters, 1st Field Artillery Brigade.

Riley’s date of 15 June, allowing for a couple of days either side, was used as a fixing point to search Australian war grave and service records.[2] Having cross-checked numerous dates and references in Riley’s text, the authors have found it to be accurate and reliable.

The authors further believe that Pearson, and a compatriot wounded that same day, are the subject of a lively story by Charles Watkins, a private in the 1/6th Battalion Lancashire Fusiliers. He tells of two Australian artillerymen joining him at his sniper’s post and insisting on ‘having a go.’ Watkins says that one was killed, the other wounded.

The war diary of Headquarters, 1st Australian Field Artillery Brigade, records the following casualties for 15 June 1915:

‘Gr Pearson BHQ killed. Br Felstead 2nd Bty wounded.’

What follows is the extract from Charles Watkins’ privately-printed book Lost Endeavour that we believe tells of the fate of Gunner Pearson and Bombardier William Herbert Felstead.

It should be noted that Watkins wrote his book more than 50 years after the Gallipoli campaign. It is not a reliable source for details like dates and names. Watkins himself says that Lost Endeavour ‘is in no way an historic account.’ His description of the two Anzacs is probably an amalgam of many encounters with Australian soldiers, but the essence of the story is likely to be true. Watkins was an early member of the Gallipoli Association, established in 1969 by a veteran of the campaign, and 13 extracts from his book were published in the association’s journal, The Gallipolian. The stories passed muster with those who were there.

The ‘Cobbers’ by Charles Watkins, 6th Bn Lancs Fusiliers

I was on a special and lousy, thankless duty one day in a little ‘sap’ (or small trench) abutting forward at right angles from our front line.[3] At the end of this little sap – about 20 yards in front of our front line – was fixed a sniper’s hidey-hole – an inch-thick steel plate with an aperture in it just large enough to poke a rifle through. You swivelled aside a little piece of the same inch-thick steel, and designed just large enough to overlap the aperture when not in use, poked your rifle through, took a quick sight at anything moving in the Turkish lines ahead, and try a quick shot, making sure you’re back to safety and with the aperture closed again, and all this before you can count ‘ten’ – otherwise you’d get one back through the aperture. For like I told you, these Turkish sharp-shooters are terrific.

All around the aperture the steel plate was dented by Turkish bullets that had thudded up against it, and even the piece of steel that swivelled over the aperture – even that was dented and bashed. After two or three hours of this duty and if you survived your first experience of it, you knew almost to the split second how long you could remain poised for a shot and be able to dodge back safely again. It was a job nobody really liked, but if you were doing it, it became a sort of challenge and in a weird sort of way you found it rather stimulating.

But if the bloke on duty lingers overlong in taking his pot-shot at the Turks, then some Mum back in England will be taking a hurried trip to the local dressmakers – ‘Mourning Orders Promptly Executed’ – to get fitted with one of those shiny black dresses. And she’ll listen uncomprehendingly to the Parson when he calls around that evening to comfort her, and talk about it being ‘God’s Will’. Bitter and twisted, she, in her simple way will wonder how can it be the will of God that all this should happen to her to lose her only son, and him being such a nice lad an’ all. For grief affects us that way.

But don’t take these Parsons too seriously, Ma’am. They’re a right lot of … so-and-so’s. An earthquake – and thousands crushed and buried; a flood – and hundreds drowned; an air disaster and many burnt alive; a four-year old and blue-eyed darling knocked down by a bus … It’s all the ‘Will of God’ to these Parsons. But don’t you believe ‘em, Ma’am. This God of Abraham, Isaac and Jacob – some of us – and with the ‘stars still in our eyes’ – we still like to think of Him like you do, Ma’am – as an old-fashioned God of Love, and not as a sadistic monster obscenely planning these catastrophes.

All this rigamarole, of course, is just my long-winded way of saying that if you don’t want your own Mum to get mixed up in all this damned nonsense, you’ve got to close that aperture a bit smartish, otherwise you’ll get it where the chicken got the chopper. Like those two Aussie blokes one day when I was on this lousy bit of sniping duty. I still feel a mite responsible that two unknown Australian Mums got mixed up in all this stuff, but if you were only a Private Soldier like me, you can’t win – not ever.

Two N.C.O.s of the Australian Artillery – huge chaps – about 6' 4" and broad with it. They were seeking an Artillery observation post as far forward as possible for the next offensive of ours. That’s how they came to be in front of our front line and chatting with me. One was a Staff Sergeant and did all the talking and the other, a Corporal, just listened and didn’t say a lot. The Staff Sergeant grew intrigued with my job and wanted to have a go himself but I told him the score and that if you didn’t know the trick, you’d be a dead duck before you could look round. This seemed to peeve him – ‘didn’t want any Pommie to tell him all about shooting’. “Back in Austry-lia he could shoot the toe-nail off a ’possum’s left foot.” He was a genial smiling bloke of about 35 to 40 with a huge fair moustache, and pleasant enough to talk to, so I tried to kid him into talking about life ‘down-under’. I didn’t want any trouble round this steel plate. But he still ached to have a go and finally got real mad. As we say in the Army he ‘shoved his stripes under my nose’ and told me to hand him the rifle, “and that’s an order,” he says. So I handed over, deeming it best to say no more, and stood alongside him pissing myself with anxiety while he took a long and careful sight. Then there was a ‘plop’ and when the Corporal and I picked him up he was as dead as ever a man can be. Then the Corporal cussed and swore – said ‘I’ll get the bastard who did that to my pal’ and in spite of my protests, poked the rifle through the hole himself. I hollared for our Sergeant, who came quick. But not quick enough and the Corporal, badly wounded, was later carted off by the stretcher-bearers. The body of the Staff Sergeant was carried to our front trench and we sent word back to his Battery as to what had happened.

Sorry, you two Australian Mums. Maybe I ought to have clouted them both to stop them being so damned stupid. But striking a superior officer while on Active Service is a deadly offence. Besides, they were both much bigger than me.

Some two hours later, three friends of the dead Staff Sergeant came to carry his body away. As I’d finished my two hours sniping duty, and feeling a bit responsible for the whole business, I offered to make the fourth man and between us we carted him away with the laudable intention of carrying him to an improvised cemetery that had just been started, about a mile away. It was a very hot afternoon and after some 200 yards or so over this rough and broken country, one of the Aussies who had been the Staff Sergeant’s closest friend back home, decided “one place is as good as another once you’re gorn,” so in a tuck of the ground sheltered from rifle fire we laid our burden down and scratched out a shallow grave. A good hour’s sweating work it was, too, and punctuated all the time by homely Aussie expressions of grief and regret, and maledictions on the hot sun that scorched our labouring bodies. Alongside us, and indifferent to the proceedings, the cause of all our labours lay stiffly, his wide-open eyes coldly watching us with the baleful malevolence of the dead. Whenever I looked at him I seemed to detect in those immobile marble eyes, a frightening malignity.

“An orphan’s curse would drag to Hell

A spirit from on High,

But, oh! more horrible than that

Is the curse in a dead man’s eye.”

In between his labours of digging, the dead man’s pal continued with his lamentations. “How I’m going to face old Jack’s Mum back in Sydney, I just don’t know. Her last words to me, Tommy afore we left, were ‘Keep an eye on him, won’t you. He’s a bit headstrong. Promise me you’ll keep an eye on him’.” He gave a deep sigh and rested from his digging for a time, squatting on his haunches and regarding his dead pal. “You always was a cocky bastard, wasn’t you, Jack?” he said kindly, and wagged his head reproachfully.

It was a macabre scene – this bare-headed, big, live Aussie – his sun-browned torso glistening with sweat, squatting alongside his indifferent dead pal and carrying on a reminiscent monologue of old times together. “Remember that sheep farmer, Jack, who tried to gyp us of the week’s pay he owed us for shearing, and the way you held him upside down to empty his pockets. And then the way you chucked him into the sheep-dip trough after, I thought I’d ‘a died laughing.” Chuckling reminiscences like this went on for a few minutes – and I sat and watched ’em – an interested spectator of these two Aussies, the live and the dead, in comradely communion. Somehow, death doesn’t seem to have the same dreadful sad finality among the irreligious soldiery as it does with their more religious brethren. It’s more as if one of their gang had been posted away on detached duty. Maybe it’s this attitude that enables them to survive, while still keeping their sanity, the daily harvest of the grim Reaper. Or maybe it is that in the blind ignorance of the teachings of religion itself, they’ve stumbled accidentally on the real truth of the matter. I dunno.

Then I blurted out what I considered to be my own share of responsibility for this tragedy. But the dead man’s pal laughed this aside. “You don’t think, do you Tommy, that an Austry-lian boy is going to let any Pommie bastard stop him doing what he wants to do.” Switching suddenly to serious and solemn vein, “Well, I guess we'd better do old Jack the honours,” and we laid him in his shallow grave.

Then the Aussie unstrapped his wide-brimmed feathered slouch hat from the top of his pack, straightened out some of the creases and knocked a cloud of dust off it before solemnly donning it, stood alongside the grave for a few seconds, then just as solemnly doffed it. The proprieties of interment thus duly observed and completed to his satisfaction, he said, “I suppose someone should say a bit of a prayer. Any of you blokes know any – I’ve forgotten all mine.” There was a shuffle of denial from the other two Aussies, so I volunteered the Lord’s Prayer, wondering at the time how many others from this place had gone to meet Him, ‘which art in Heaven’, and armed with no more letters of introduction than this brief prayer. Then we filled in the space above the dead Aussie, and yet another hump appeared on this sacred ground of lost endeavour.

The other two Aussies were mostly silent, and didn’t say much except for an occasional interjection of the soldier’s favourite obituary, “Poor Bastard.”

The dead man’s pal raised the point of marking the grave with something – “a bit of a cross or something.” I thought of all the other “little bits of crosses” scattered all over the Peninsula in all sorts of odd places – little packets of soldier bones clamouring for immortality by means of little wooden crosses, crudely fashioned from pieces of biscuit box wood, and with their identities scrawled in indelible pencil that the rains had by now smeared into indecipherable smudges, and said, “Did it matter much?”

But this great big hunk of sunburnt Australian manhood was genuinely and sentimentally shocked. “Did it matter much? There’s a little lady back in Sydney, Tommy, I’ve got to face when I get back. How can I tell her her boy’s in an unmarked grave?” He seemed appalled at my callousness. One of the other Aussies begged a bit of wood from a cook-house some distance away and returned in triumph, and with our bayonets we cut some sticks of wood and with the aid of a spare bootlace, fashioned a rough cross and pegged out our dead man’s claim to immortality. With much licking of the stub of an indelible pencil he recorded the name of the dead Staff Sergeant and stood back to admire his handiwork. “That’s better, old-timer. Now I can tell yer Ma you’re all tucked up nice and comfy. How many ‘l’s in killed, Tommy?” I told him; also, told him how to spell ‘action’. As regards the date, we hazarded a guess, but the Aussie thought accuracy was of first importance, and after canvassing the opinion of a few chaps idly watching we split the difference and settled for July 10th, 1915. Even now, the Aussie wasn’t completely satisfied. He’d still got some more of the stub of the pencil left and the urge for registering immortality was strong upon him. “Shouldn’t there be some other words after the name, Tommy? A sort of good wish?”

“Requiescat in pace,” I suggested.

“Come again, Tommy?” said the Aussie, puzzled. “What’s them letters they put after a bloke’s name – when he’s dead?”

“R.I.P?”

“Yes, that’s it, Tommy, What’s it mean?”

“Oh, about the same, I guess.”

So Staff Sergeant Ballantyne, through an unfortunate error in calligraphy, became Staff Sergeant BALLANTYNE-RIP, which could cause all sorts of passport delays at the Final Frontier. Fortunately, the Feathered Frontier Guards in Shining White are well used to the vagaries of the Anglo-Saxon race and no doubt all would be put right eventually.

One of the Aussies had some fags and we sat around a bit and smoked. Oh! blessed and mighty rare weed – how it mellowed us. Discussions ranged about the future life of Staff Sergeant Ballantyne-Rip. “Wonder what it's like up there,” said the talkative Aussie, waving an arm vaguely skywards.

“Rum sort of place, from all I gather,” one of the others said. “Sitting round all day singing bleeding hymns and playing harps. Praising God and all that mush.”

“What do you think, Tommy?” the talkative one asked me.

Startled, I had to admit that I didn’t knew much about it, but Sunday School teaching memories seemed to corroborate the description already given. “Much about like your mate says,” I opined.

The Aussie appeared troubled. “No Sheilas?” he asked.

“Sheilas?”

“Girls. Bints,” the Aussie explained impatiently. “Ain’t there none there? And what about booze and fags? Ain’t there none there, too?”

I said I didn’t know, but I thought not. Memories of childhood Band of Hope Temperance Meetings were still strongly with me, with drink as the Devil’s Handmaiden.

The Aussie was pensive for a bit, then gave a long low chuckle. “No Sheilas, no booze, no fags. Cor! I can just see old Jack’s face when he finds out.” Then he corrected his unseemly merriment and said piously, “Poor old Jack. And as nice a bloke as ever you could wish to meet.”

Gunner 3513 Stanley Pearson, Headquarters, 1st Field Artillery Brigade

‘Staff Sergeant Jack Ballantyne’ is probably Stanley Stephen Crawte Pearson, born 1888 or 1889 in Hornsey, north London, the son of Stephen Crawte, a clerk, and Marie Pearson.

He joined the Royal Navy in 1905, serving on a number of ships and attaining the rank of able seaman. He also accumulated 37 days in the cells. On 1 July 1913, Pearson deserted from HMS Cambrian while she was berthed in Sydney Harbour. His name and a description (‘has water on the knee, wears elastic bandage’) was published in the New South Wales Police Gazette.

Pearson enlisted with the AIF in December 1914 at Liverpool in western Sydney. He was 28 or 29 years of age and understandably circumspect with his personal information, giving his birthplace as Perth, WA. He did however volunteer the fact that he had eight years’ service in the Royal Navy, gilding the lily perhaps when describing himself as a leading seaman and gun layer.

Pearson was first assigned to the Divisional Ammunition Column, then transferred to the 1st Field Artillery Brigade Ammunition Column on 20 March 1915. His service record states that he was attached to Headquarters, 1st FAB, when killed in action at Gallipoli on 15 June 1915, and buried by a chaplain in the Royal Naval Division (RND) cemetery near Achi Baba Nullah and Romanos Well. Today his name is listed on Special Memorial A. 35 (‘presumed to be buried but grave not identified’) in Skew Bridge Cemetery where graves from the RND cemetery were concentrated post-war.

Pearson had written his will the day before the Anzac landing. He left the whole of his property and effects to Miss Ruby Luckman of Tempe, Sydney. In the early 1920s, the AIF base records office contacted Ms Luckman to determine if Pearson had any blood relations to whom they could send his medals. A notice was also published in the newspapers. Ms Luckman replied on 21 April 1921, informing them of a brother, Steve Crawte Pearson, who had been on HMS Encounter at the time of the war. She thought Pearson’s parents had a farm somewhere in WA. Having traced Ms Luckman, the base depot sent her the package with Pearson’s effects. These included letters, photos, a watch (damaged) and a French war medal and clasp.

Pearson’s brother, Sailmaker’s Mate Stephen Crawte Pearson, O.N. 3889, serving on HMAS Melbourne, was tracked down via the navy office, and Stephen made contact with his parents in Ashfield, Sydney.

In his letter to the records office, Pearson’s father wrote:

‘One of my sons Stanley Crawte Pearson joined up [in] the early part of the war, since that time we have had no news at all from him, and should not be surprised if the soldier S Pearson spoken of in your letter is my son.’

He described Pearson’s distinctive tattoos and said that previous to enlisting in the AIF he’d been in the navy.

‘I should be glad to know if the same person is my son or not, as his Mother has been very anxious for news concerning him.’

Confirmation came, and Marie Pearson did indeed receive her son’s death scroll and medals, and a gratuity.

The reader will spot many discrepancies, like rank and date, in the picture painted by Charles Watkins. As for the physical description, it is probably coloured by time and encounters with other Australian soldiers. We know from his attestation papers that Gunner Pearson was 5 feet 8 inches, whereas the imposing staff sergeant was ‘huge … about 6' 4" and broad with it’. Having said that, Pearson was well over the average height of men in the British 42nd Division, many of whom were six inches shorter. And would Pearson have had quite the pommy-baiting drawl? He’d only been in Australia a couple of years at most. But the attitude Watkins describes certainly chimes with what we know of Pearson’s life to that date.

As for the operational context, Watkins says the Australians were scouting for a forward observation post ahead of a planned attack. The war diary for 1st FAB confirms that the Anzac artillerymen assigned to this sector had several schemes planned for the days ahead. But there is also a pertinent reference to sniping in the entry for 15 June:

‘Party of sharpshooters from 1st Bde take up positions in forward trenches for sniping purposes, under Br Rossiter, BHQ.’

Pearson and Felstead might’ve been ordered to this task. Or perhaps, as Watkins says, they were simply after adventure.

Bombardier 195 William Herbert Felstead, 2nd Battery, 1st Field Artillery Brigade

Pearson’s compatriot was 10 years younger but coincidentally also born in north London, in Finchley, just a few kilometres from Pearson’s birthplace.

William Herbert ‘Bill’ Felstead enlisted in the AIF in Sydney on 28 August 1914 when just shy of 20 years of age. He was a warehouseman, close to six feet in height, with pre-war militia service with the Australian garrison artillery. His father lived on Clarence Street in Sydney’s city centre.

Felstead embarked overseas on 18 October 1914 and would’ve undertaken further training in Egypt before reaching Gallipoli. His service record reveals little about his experience on the peninsula except that he was wounded (‘B.W. left foot’) on an indeterminate date. Thanks to the 1st FAB war diary, we know that he was wounded on 15 June 1915. The service record states that he was returned to duty on 7 July. Felstead’s time at Gallipoli ended on 6 October 1915 when evacuated sick (‘pyrexia’) to England.

On 18 January 1916, he was discharged from the AIF (‘military character very good’) to be appointed to a commission in the Royal Field Artillery. Felstead transferred back to the AIF in November 1916 as a second lieutenant, serving on the Western Front with the field artillery. In June 1918, Lieutenant Felstead was granted the temporary rank of captain while commanding a trench mortar battery. He returned to Australia in May 1919 and was living in Redan Street, Mosman, in 1967. He died in 1971.

Private 8878 (later 403846) Charles Watkins, Lancashire Fusiliers

Charles Watkins was born in England on 3 November 1895, son of Charles and Mary Ann Watkins. He attended secondary school in Rochdale, Lancashire, from 1909 to 1912, then worked as a card room hand in a cotton mill.

Watkins joined the Territorial Force on 7 May 1913 when 17 and a half years of age. He embarked with the 1/6th Battalion Lancashire Fusiliers for Egypt on 24 September 1914 when the 42nd (East Lancashire) Division, of which his battalion formed a part, was the first territorial division to embark for overseas service. Watkins writes:

I left school at the age of 15, to go and work in a foul Lancashire cotton mill, 12 hours a day. As a Territorial soldier (volunteer) I was mobilised at the outbreak of War One on August 4th 1914, and went abroad to the Middle East theatre of war at once. So the war itself was for me, and for most of us, a deliverance from slavery, and as such was a welcome relief.

After training in Egypt and fighting at Gallipoli, Watkins entered the Royal Flying Corps on 2 September 1916 as air mechanic second class. His qualifications are recorded as:

‘Associate of Arts knowledge of French and Arabic, book-keeping, shorthand, typing. Since joining RFC – organisational and administration, brigade office. Also general staff work, clerical work.’

Watkins applied, unsuccessfully at first, for advancement to air mechanic first class and corporal. The latter promotion came on 1 December 1917. Watkins attended flight cadet school in Cairo and graduated as balloon observer on 8 June 1918. He was granted a temporary commission as 2nd lieutenant on 26 July 1918. He transferred from 55 Kite Balloon Section to 22 Kite Balloon Company in Salonika in September 1918.

For me, it was the most enjoyable time of the war – so much so that I could have wept when the war ended, for I loved the job so much.’

In 1939, Watkins was married and living in Portsmouth with two children (he later had a third). Watkins gave his occupation as ‘air service clerk Royal Air Force’ and ‘civil servant’.

He died aged 93 in 1989.

FFFAIF connections

The author’s copy of Watkins’ book Lost Endeavour was purchased with two letters from Watkins tucked into the pages. They are addressed to Colonel Carl K. Mahakian of the US Marine Corps Reserve in Burbank, California.[4]

On 1 October 1985, Watkins writes:

‘I will put you in touch with a Colonel of the Australian Forces who fought against the Japs in the Burma campaign. He now lives in England and is a great personal friend of mine. He is also a prolific author, and his own book “DAMN THE DARDANELLES” is, in my opinion, the best historic account of the whole campaign.’

Watkins and John Laffin presumably met through the Gallipoli Association, whose journal The Gallipolian carried numerous extracts from Watkins’ book. Laffin acknowledges in Damn the Dardanelles! that he ‘made much use of veterans’ recollections published in the association’s quarterly journal.’ Among the recollections used by Laffin are four attributed to ‘my friend’ Charles Watkins. ‘His description of life at Helles,’ wrote Laffin, ‘is one of the most vivid in Gallipoli literature.’

Laffin joined the Gallipoli Association as an Associate Member in 1978. (Full membership was reserved for Gallipoli veterans.) According to the association’s journal, his mother Nellie Alfreda Laffin (née Pike) joined as a full member, the only nurse to do so. She served, as members would know, during the Gallipoli Campaign with the Australian Army Nursing Service at Lemnos. (‘Nell’ died on 15 June 1980.)

Finally, the authors hope that this article provides the answer to a question posed in Digger more than 15 years ago. A short excerpt from Watkins’ story of the two Australian artillerymen was presented on page 36 of issue 13, December 2005, with the following request:

‘The Sergeant is identified by Watkins as Sergeant Ballantyne; however he does not appear on the Nominal Roll. Perhaps a member can establish the Sergeant’s identity.’

Sources

Alec Riley, Gallipoli Diary 1915 (Mosman, NSW: Little Gully Publishing, 2021)

Charles Watkins, Lost Endeavour: A survivor’s account of the ill-fated Gallipoli Campaign (Eldenbridge, Kent: Promotion House, 1970)

Correspondence between Charles Watkins and Col. Carl K. Mahakian, 1985 (author’s collection)

E.H.W. Banner, review of Damn the Dardanelles! in The Gallipolian, issue 35, 1981 (Gallipoli Association)

Gallipoli Association journal archive, available online to members at gallipoli-association.org

John Laffin, Damn the Dardanelles! (London: Osprey, 1980)

Service records, National Archives of Australia (series B2455) and National Archives UK (series AIR 76 and AIR 79).

War diary, Headquarters, 1st Australian Field Artillery Brigade, June 1915 (Australian War Memorial, AWM4 13/29/7)

Footnotes

[ (Opens in a new window)1] The 2nd Australian Infantry Brigade, who fought in the Second Battle of Krithia on 8 May 1915, had returned to Anzac by this time.

[ (Opens in a new window)2] The authors reviewed all Australian artillerymen in the Commonwealth War Graves Commission database who are commemorated in Turkey on the Helles Memorial and in the cemeteries Lancashire Landing, Pink Farm, Redoubt, Skew Bridge and V Beach. War diaries and service records were consulted for each man. Absolute certainty is not possible but the circumstantial evidence suggests Pearson is ‘probable’.

[ (Opens in a new window)3] Watkins’ unit, the 1/6th Lancs Fusiliers, had been holding the right sub-section of the firing-line which stretched from Achi Baba Nullah on the right to the communication trench that ran along the western side of the Vineyard. The British firing-line ran along the southern end of the Vineyard and, before the advance of 4 June and the capture of the then Turkish firing-line, several similar communication trenches ran back towards the Turkish support lines. These communication trenches were subsequently blocked with barricades and Watkins may well have been manning a loophole in one. Although his battalion had been relieved from the firing-line by the 1/8th Lancs Fusiliers around 3.30 p.m. on the previous day, Watkins may have remained behind temporarily with other ‘snipers’ to pass on hard-earned knowledge and operating procedures relating to the posts. That he was able to accompany the Australian burial party (under normal circumstances an ‘other rank’ would not have been allowed to leave the firing-line) suggests he had been relieved from the post to allow him to return to his battalion, which was then in the Redoubt Line some 430 yards further back.

[ (Opens in a new window)4] Colonel Mahakian (1926–2015) served in World War II, the Korean War and the Vietnam War. He also worked in radio, television and film, winning two Emmy Awards. The USMC’s interest in the Gallipoli campaign is well known and may be the reason for Mahakian’s interest in Watkins’ book. However, his extensive work in Hollywood does raise an intriguing thought… was he thinking of pitching a film on the campaign?