Newsletter No 10 - Job Maseko: The Unsung Hero of World War II

Good morning, afternoon and evening, family,

Welcome to Newsletter No 10.

Im continuing my theme of sharing stories deemed unworthy by the social media algorithms, and so this week, I'm sharing the incredible story of Job Maseko a South African soldier, who destroyed a German ship with a tin can during WWII.

I came across the story I’m about to share through my good friend and long-time collaborator, Updesh. An amazing historian in his own right, Updesh, or Uppy as I call him, sent me a Twitter thread about Job, and my insatiable appetite for a good story took over from there. So please take a moment to learn about this Incredible Man.

Who was Job Maseko?

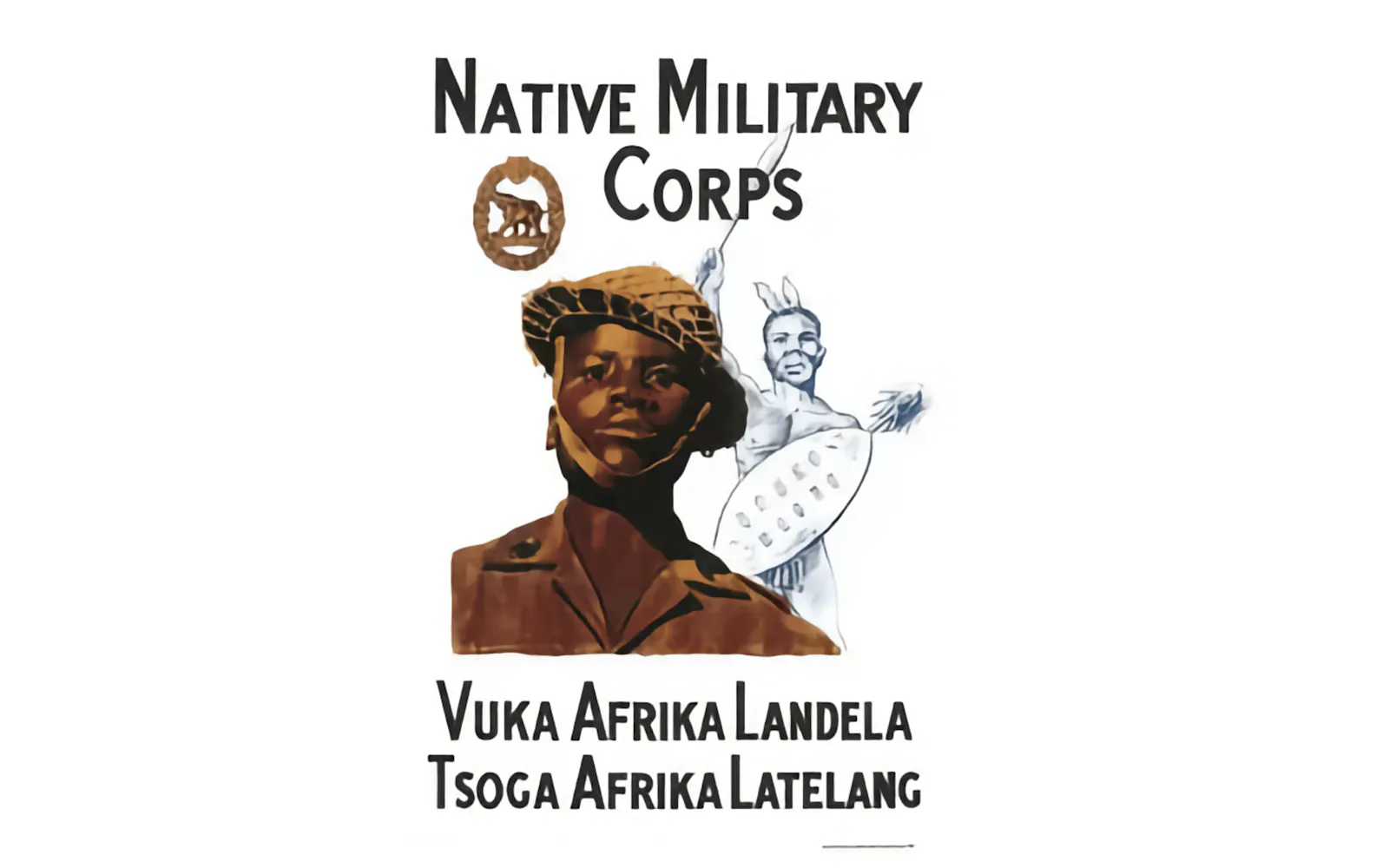

Job Maseko was born in 1917 in Springs, a town near Johannesburg. He grew up in poverty and worked as a miner before joining the South African Army in 1940. He was assigned to the Native Military Corps (NMC), a unit composed of black soldiers who were not allowed to carry weapons or fight on the front lines. Instead, they served as labourers, drivers, cooks and stretcher-bearers for the white troops.

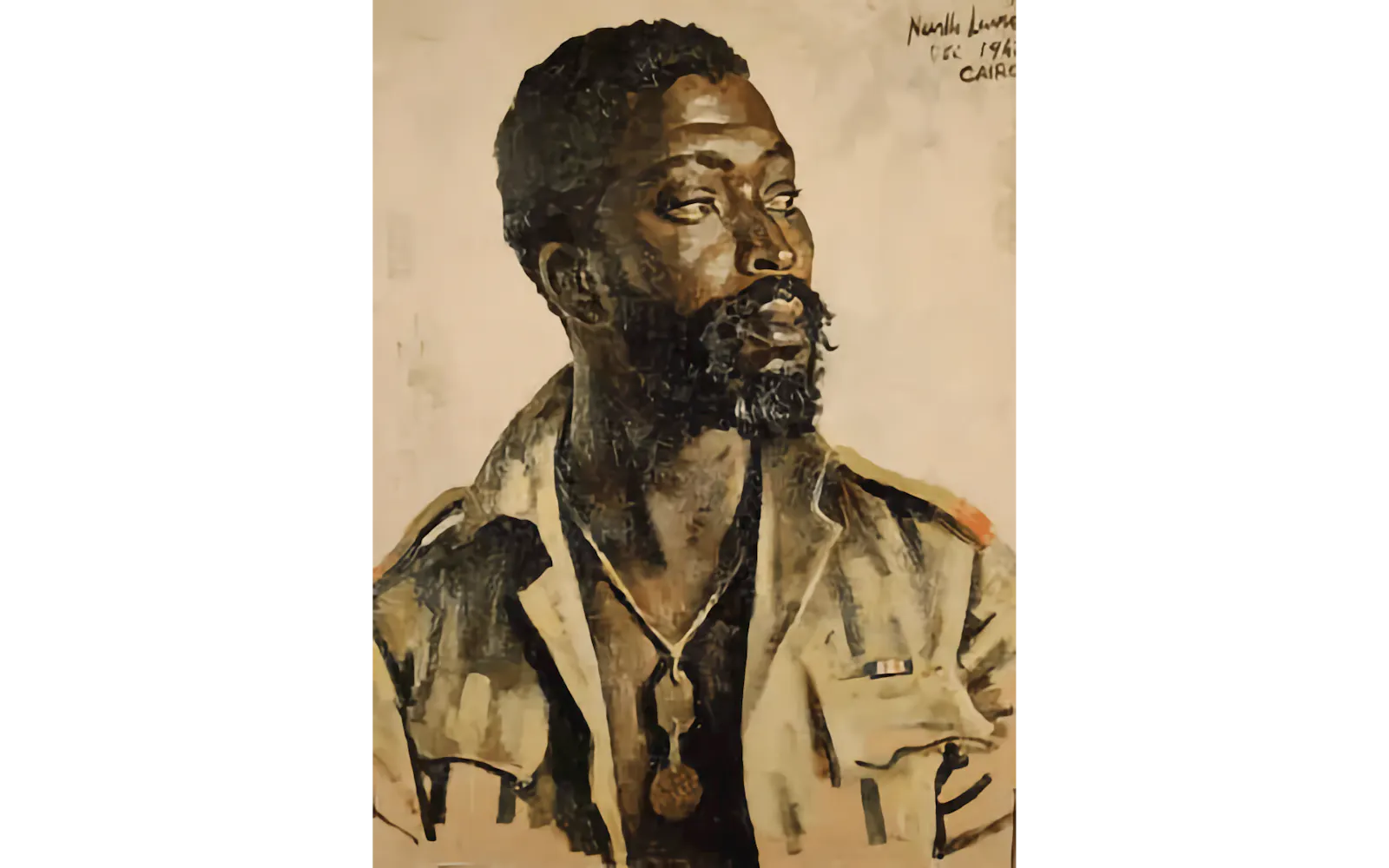

Maseko volunteered to serve overseas and was sent to North Africa with the South African 2nd Infantry Division. He participated in several battles against the German-led Axis forces, including Operation Crusader and the Siege of Tobruk. He showed courage and bravery by rescuing wounded men under heavy fire and risking his life to deliver supplies and messages.

How did he blow up a German ship?

In June 1942, Tobruk fell to the Germans after a surprise attack by Field Marshal Erwin Rommel's Afrika Korps. Maseko was among the 10,722 South Africans who were captured and taken prisoner by the enemy. He was transported to an Italian-run POW camp near Tobruk harbour, where he endured harsh conditions and mistreatment.

Despite being imprisoned, Maseko did not lose his spirit or his patriotism. He secretly joined a group of fellow POWs who planned to escape from the camp. He also devised a scheme to sabotage one of the German ships that were docked at Tobruk port.

Using materials he scavenged from the camp, such as tin cans, cordite (gunpowder) and a fuse made from a long sock soaked in petrol, he made an improvised explosive device (IED). He then managed to sneak out of the camp at night with two other POWs and reached the harbour area.

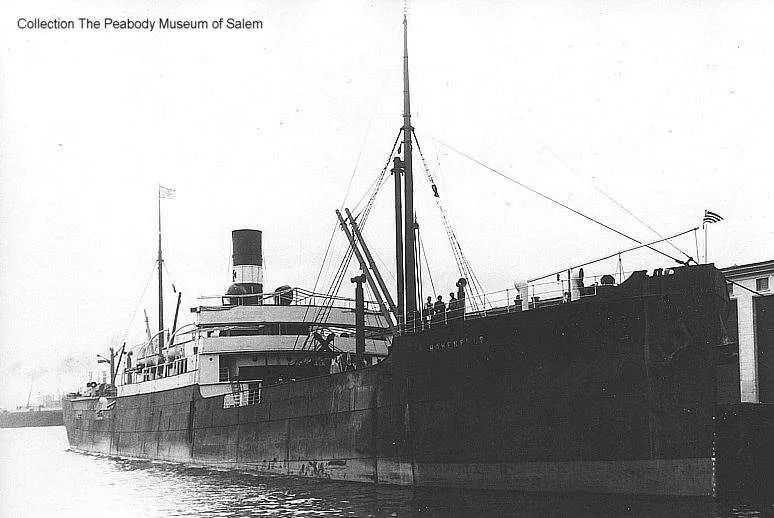

There he found an unguarded freighter named SS Hohenfels, which was loaded with ammunition, fuel and other supplies for Rommel's army. He climbed aboard the ship unnoticed and placed his IED inside one of its fuel tanks. He then lit the fuse and ran back to shore before it exploded.

The blast caused a huge fire that engulfed the ship and its cargo. The explosion also triggered secondary explosions on nearby vessels. The damage was so severe that it took several days for firefighters to put out the flames. The Germans were shocked by this unexpected attack that disrupted their supply line.

What happened to him afterwards?

Maseko returned safely to his camp without being detected by anyone. However, he could not keep his deed secret for long as word spread among other POWs who witnessed or heard about it. His fellow prisoners hailed him as a hero and nicknamed him "Bigboy" for his courage.

His act of sabotage also reached the ears of some British officers, who were impressed by his skill and ingenuity. They recommended him for the Victoria Cross (VC), which is the highest military honour awarded for valour "in the face of the enemy".However, Maseko did not receive the VC because of the racial policies of the South African government at the time.

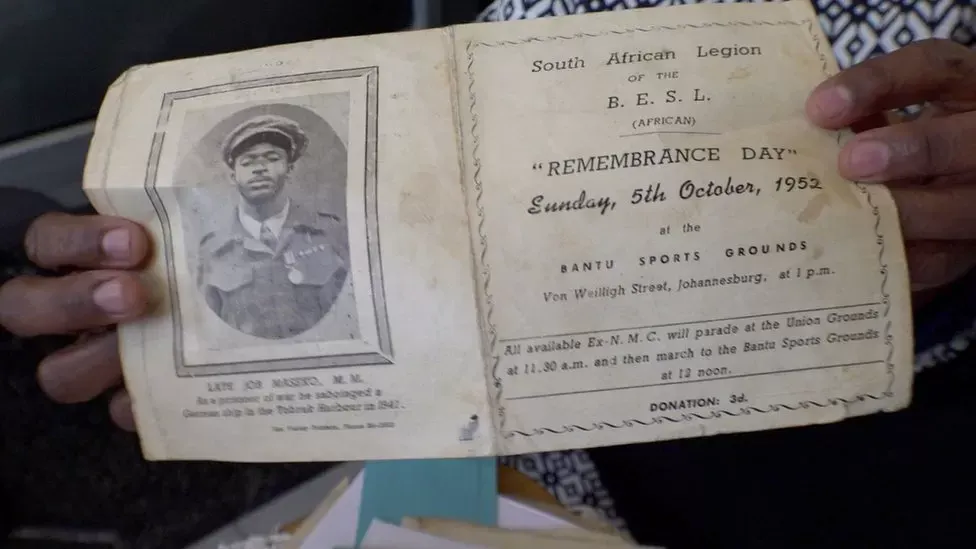

The NMC soldiers were considered inferior and subordinate to the white troops, and they were denied any combat awards. Instead, Maseko received the Military Medal (MM), which is a lower-level decoration. He accepted it gracefully, but many felt he deserved more recognition for his extraordinary feat. Maseko remained a prisoner until the end of the war in 1945.

Maseko returned to South Africa in 1946 with hopes of a better life. He hoped his service and sacrifice for his country would be recognized and rewarded. He hoped he would be treated as an equal citizen in his land. But he soon realized that nothing had changed for black people under apartheid.

He faced discrimination, poverty and oppression. He could not find decent work or housing. He could not vote or travel freely. He could not enjoy the same rights and privileges as white people who had fought alongside him or benefited from his actions.

Maseko became disillusioned and bitter. He turned to alcohol to cope with his frustration and despair. Suffering from post-traumatic stress disorder and depression, he eventually lost contact with his family and friends.

He died tragically in 1952 when he was hit by a train near Springs, where he lived in a shack. His death was barely noticed by the authorities or the media, and his medal was stolen from his widow's home shortly after his funeral.

His story was almost forgotten until recently when some historians and activists began campaigning for his recognition and honouring of his contribution to the war effort.

It’s time Maseko’s valour is recognised by a posthumous award of a higher military decoration, such as the Victoria Cross or Distinguished Conduct Medal.

It’s time he is given a proper burial site with a memorial plaque or statue, and it’s time that he be remembered as one of South Africa's great heroes.

Job Maseko deserves more than what he got from his country. He deserves more than what history has given him so far. He deserves our respect, gratitude and admiration for his courage, bravery and patriotism.

So if you are learning about him for the first time today, please share his story with a friend, loved one or work colleague because if world governments won’t recognise him or his contributions, we certainly can.

If you think this should be turned into a podcast episode or social media post, please reply to this email, letting me know why.

This is the part of the newsletter where I ask you to join my membership site.

The content I make is free to consume but not free to make; it costs me time, money and a huge emotional investment to do what I do, so if you enjoy my work and want to join me on my learning journey, join my membership platform.

By doing so, you’ll be replenishing both my emotional and financial bank accounts.

Until next week, stay strong, stay wise, and remember Black History is World History.

Blessings,

KK