Newsletter 13 The Aba Women's War (1929-1930):

Good morning, afternoon and evening, family,

This is King Kurus, and I'm excited to share the second audio edition of my Black History Buff newsletter with you. I'm incredibly grateful to all of you who reached out with your kind words and support after the first recording went out. It reached over 2,300 people, and the feedback has been amazing! Help grow this community of history lovers by forwarding this to a friend or colleague today.

Featured story:

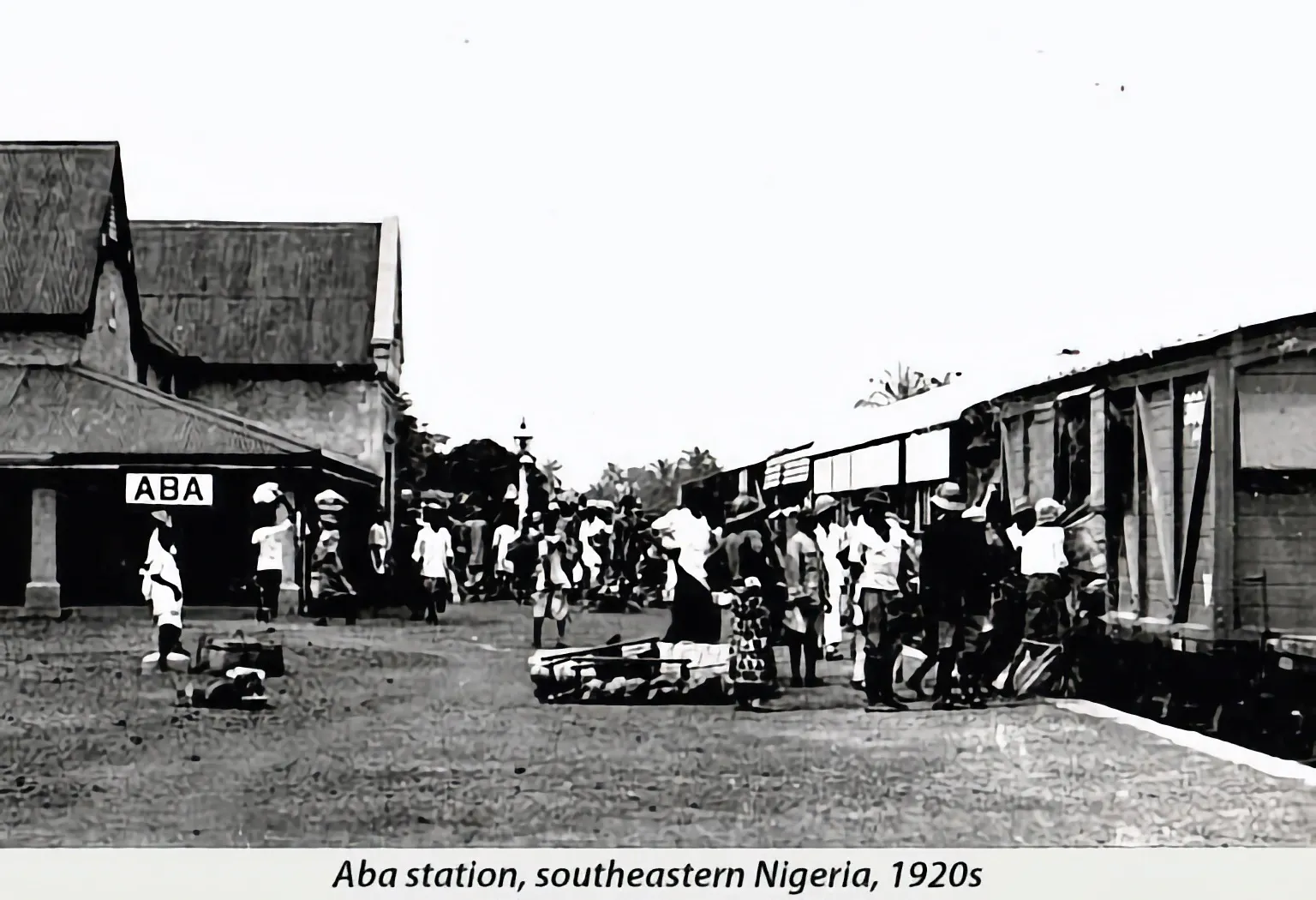

This edition delves into a remarkable and transformative event in Nigerian history - the Aba Women's War of 1929. This uprising, also known as the Women's War or Ogu Umunwanyi, played a significant role in shaping the course of Nigeria's colonial and post-colonial era.

The Aba Women's War (1929-1930): A Turning Point for Women in West Africa

The Aba Women's War, also known as Ogu Ndem or the Women's War, was a significant revolt staged by women in West Africa. Organized by rural women from the Owerri and Calabar provinces in present-day Nigeria, this revolt demonstrated the power Nigerian women wielded to influence politics as they organized against the abusive British colonial forces stationed in their region.

The revolt had several causes, but the primary one was the harsh economic policies imposed on the Nigerian people by the British. In particular, taxation became a point of contention during the Great Depression. In need of funds, the British decided to extract wealth from Africans.

The roots of the Women's War can be traced back to January 1, 1914, when the first Nigerian colonial governor, Lord Lugard, implemented the system of indirect rule in Southern Nigeria. Under his plan, British administrators ruled locally through warrant chiefs, who were essentially Igbo men appointed by the governor. This broke from the traditional method of electing Igbo rulers in a local vote. Women in Nigeria previously held political power and influence through marriage, elite societal status, and control of the markets. In addition, men and women shared domestic duties, making them equal members of society.

The British perceived this social structure as chaotic and disorderly, and they set about implementing a patriarchal system that excluded women from power. Within a few years, the appointed warrant chiefs became increasingly oppressive, seizing property, imposing harsh local regulations, and imprisoning anyone who openly criticized them. Although anger was directed towards the warrant chiefs, most Nigerians understood that the true source of their power was the British colonial administrators.

Colonial administrators further exacerbated the community's sense of injustice when they imposed direct taxation on men. This direct taxation significantly increased pressure on family finances. When rumours began to circulate that the previously tax-exempt women would soon be taxed, tensions flared.

The tipping point occurred when a census taker attempted to question a woman in the village of Oloko. A widow named Nwanyeruwa was asked by a man named Emeruwa to provide the number of people, goats, and sheep in her household for the national census. Suspecting that this was a ploy by the British to implement a new tax on women, Nwanyeruwa angrily asked Emeruwa if his mother had been counted. This interaction led to a physical altercation, which prompted Nwanyeruwa to raise the alarm and gather the women of the village.

As the story spread, women from nearby villages joined the cause, and within a few days, 10,000 women gathered in the town. They began a series of protests against the warrant chiefs, using various tactics, including one called "sitting on a man."

"Sitting on a man," or making war on a man, was a long-held tradition used to address injustice in Nigerian society. Women using this tactic would surround the home of the man in question, dancing and singing songs that insulted his manhood while destroying anything he valued, which at times included his home. This practice continued until the man repented and changed his ways. Men who were "sat on" could not expect support from other men for fear of invoking the women's wrath upon themselves.

In the case of the Warrant Chiefs, the women not only danced and sang around their houses and offices but also followed them everywhere, invading their space and forcing them to pay attention. The women demanded that the colonial government either abolish the taxation or the local warrant chief resign his position.

Women throughout Igboland took to the streets in demonstrations, and sit-down strikes occurred across all major Igboland towns and cities supporting the movement. In an attempt to appease the women, the British put one of the Warrant Chiefs on trial for assaulting two women during a revolt in Okolo. This temporarily eased tensions, but the situation escalated again when a reckless British driver hit and killed two protesters in Aba.

In response, the women burned down government offices and European-owned businesses. The damage to British and European interests became so severe that the army had to be called in to suppress the rioting women. Recognizing the power of this women's movement, the British eventually sought a compromise: they would never again ask women to pay taxes if the revolt ended.

The Aba Women's War played a crucial part in shaping the role of women in Nigerian society and helped to usher in the national political movements that eventually led to Nigerian independence. Many lives were lost, and many more women were injured in this revolt, but their determination and resilience led to a victory, albeit temporary.

This story is an important reminder of the critical role women, particularly black women, have played in the fight against oppressive regimes. The women of the Aba Women's War were not willing to be oppressed in their own homes or lands, and they fought back using every method available to them. Their inspiring legacy continues to resonate today as women around the world continue to fight for their rights and equality.

The Aba Women's War is particularly relevant in the context of modern movements like Black Lives Matter and the SAR movement. It highlights how women, especially black women, have always been at the forefront of the fight against oppressive systems. Their strength and determination have been a driving force for change historically and in contemporary times.

Reflecting on personal experiences, it becomes clear that women have consistently fought for the rights and well-being of their loved ones, whether it be in school, the workplace, or encounters with authorities. The story of Marcus Garvey and how his wife, Amy Garvey, used herself as a human shield to stop an assassin's bullet is another example of the bravery and sacrifice of women throughout history. Such stories, though not told as often as they should be, are vital reminders of women's invaluable role in pursuing justice and equality.

In conclusion, the Aba Women's War is a powerful and inspiring story of how women in Nigeria united and fought against an oppressive colonial regime. Their resilience and determination ultimately led to changes in their society and contributed to the broader fight for independence. The legacy of these women serves as a reminder of the strength and courage of women worldwide who continue to fight for their rights and the rights of others.

Links & resources:

You can learn more about the Aba Womens war by reading the book Women War by Gerald Oluchi Ibe at the link below:

https://www.amazon.co.uk/Women-War-Story-Womens-1929-ebook/dp/B09F95GMPF?crid=1MHFEWWXB4MB4&keywords=the+aba+women%27s+war&qid=1679394791&returnFromLogin=1&sprefix=thew+aba+womens+war%2Caps%2C262&sr=8-1&linkCode=sl1&tag=blackhistor06-21&linkId=0df50a2439ed0af914feb326680f92da&language=en_GB&ref_=as_li_ss_tl (Opens in a new window)Support my work:

I hope you enjoyed this edition; it's a story I've wanted to share properly for a long time.

If you have gotten this far, I’d like to ask you to come with me further and consider joining my membership site. The stories I share are free to consume but not to create; they cost me time, money and a huge emotional investment to pull together, so if you enjoy my work, check out my membership platform and go deeper with me on my journey through black history. You can support my work by hitting the button below:

Thank you for being part of this journey, and I look forward to hearing from you soon!

Blessing’s

K