Queen of the Rings: Did Tolkien help Margrethe of Denmark abdicate?

[I posted this article privately for my Steady supporters on 3 January (Tolkien’s birthday) when I was first pitching it for publication. It was published in Danish by Weekendavisen on 12 January (Öffnet in neuem Fenster), the day before Queen Margrethe’s abdication, so I now make it openly available to English readers, slightly updated to reflect the fact that King Frederik has now succeeded to the throne.]

Queen Margrethe of Denmark is the first Danish monarch to abdicate for 900 years. Then again, she is also the first to be a devoted reader of The Lord of the Rings, which has wise things to say about the relinquishment of power.

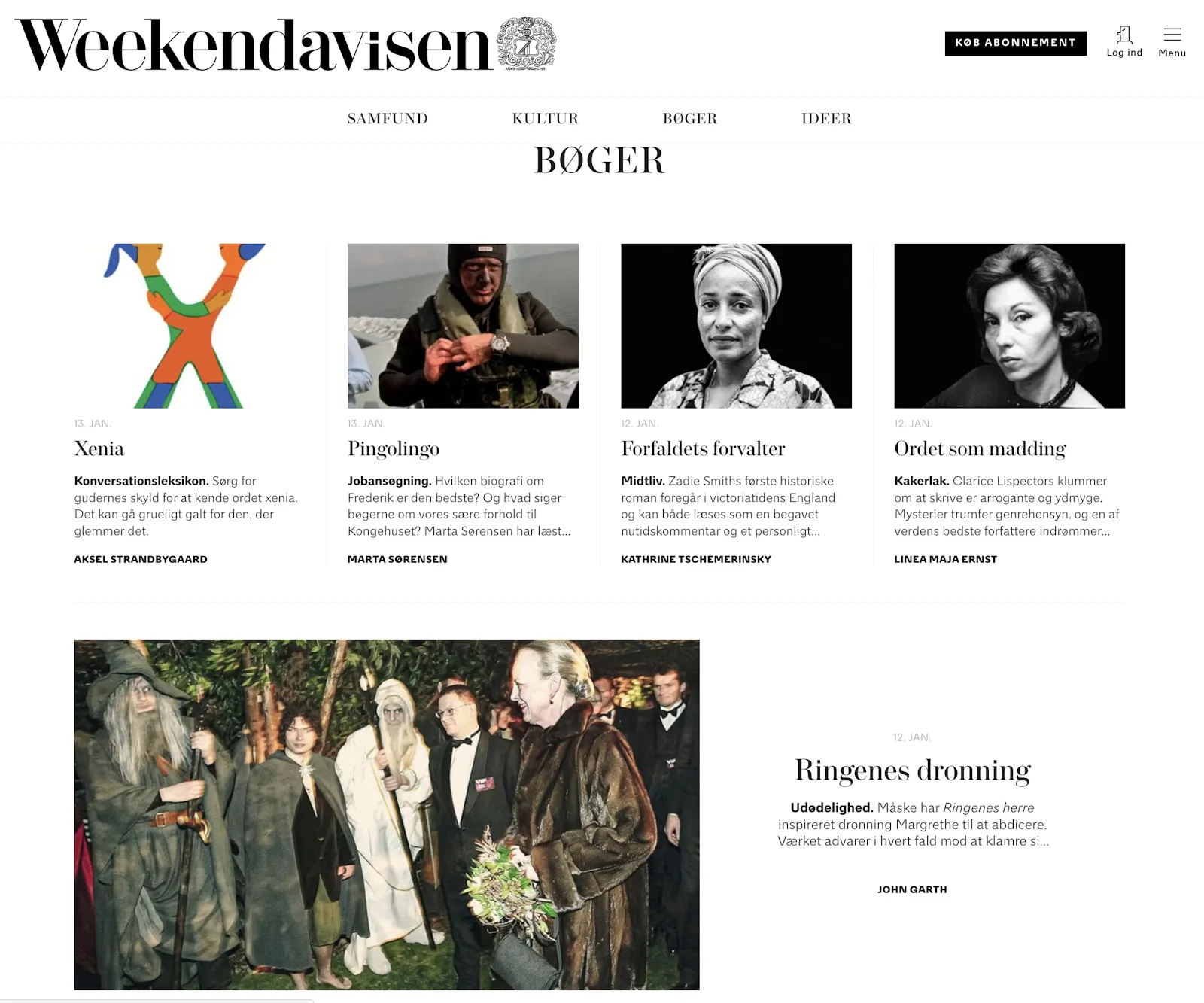

As Princess Margrethe, in 1970 she wrote to Tolkien telling him she had read the book with ‘much pleasure’ and had ‘been reading it ever since’. To show her appreciation, she sent him illustrations (Öffnet in neuem Fenster) for each chapter. Tolkien must have been especially delighted because the chief part of his own chief literary inspiration, the Anglo-Saxon poem Beowulf, is set at the royal court of Denmark.

The princess and the author corresponded for two years and she sent him her drawing of Bilbo at work on his memoirs. The elderly Tolkien (who was then facing the fact that he might never finish his own lifework, The Silmarillion) praised the way she had ‘suggested the struggle of age with a task beyond its power to complete’.

Their correspondence might have continued, but she became queen in January 1972 and Tolkien died in September 1973, aged 81. But in 1977 Queen Margrethe allowed her illustrations to be used in the Folio Society edition under a pseudonym, Ingahild Grathmer, and adapted for publication by Eric Fraser (Öffnet in neuem Fenster).

In this book to which Margrethe is devoted, the highest virtue is to relinquish power. Those defending freedom and peace against the demoniac tyrant Sauron refuse to use his own Ring of Power to defeat him. Instead they destroy it, relinquishing the chance to be masters of Middle-earth themselves.

When Margrethe first read Lord of the Rings, she had a profound connection with Arwen, betrothed to the mortal hero Aragorn: both were queens in waiting.

For real-world inspiration she had looked to Queen Elizabeth II of Britain, realising ‘that I must somehow (Öffnet in neuem Fenster) understand that I must dedicate my life to my nation like she has done’. She already knew how intimately monarchy is entwined with mortality. Elizabeth had become queen at 25 on the death of George VI. Princess Margrethe ‘hoped I wouldn't be (Öffnet in neuem Fenster) as young as that when my father died’. In the event, she was not much older, at 31.

Despite much speculation over the years, Elizabeth never abdicated, perhaps deterred by the example of her uncle, Edward VIII, who quit the throne ignominiously for an unsuitable marriage. She remained remarkably active until her death at 96 in 2022, when Queen Margrethe attended her funeral.

(Öffnet in neuem Fenster)

(Öffnet in neuem Fenster)But in her decision to abdicate the throne of Denmark to her son, the Crown Prince Frederik, Margrethe could look to The Lord of the Rings. All devotees know the almost unbearably poignant Tale of Aragorn and Arwen, tucked away in the appendices. It is precisely a reflection on mortality, wisdom, royal duty and relinquishment.

At the end of the main story, Aragorn is crowned king of Gondor and Arnor, restoring the ancient royal line of Númenor. The Tale revisits him in old age when, after long years of just rule, he tells Queen Arwen he will now relinquish both crown and life.

She asks, ‘Would you then, lord, before your time leave your people that live by your word?’

‘Not before my time,’ he replies. ‘For if I will not go now, then I must soon go perforce. And Eldarion our son is a man full-ripe for kingship.’

Aragorn looks to other royals not for inspiration, but as a dire warning. In the more ancient period dramatised in Amazon Prime’s Rings of Power, the kings of Númenor had clung to life and power until death took them unwillingly. Aragorn advises Arwen: ‘Take counsel with yourself, beloved, and ask whether you would indeed have me wait until I wither and fall from my high seat unmanned and witless.’

In this year’s New Year speech, Margrethe cited the toll of time (Öffnet in neuem Fenster) on her own health and reasoned that now is the right time ‘to pass on the responsibility to the next generation’.

Tolkien’s tale is all the more poignant because of the existence of elvish immortality in Middle-earth. The kings of Númenor envied immortality and ultimately tried to seize it for themselves – triggering the destruction of their nation.

In contrast, elf-born Arwen has relinquished her own immortality to marry Aragorn. Now she sees the bitter end of that decision, ‘the loss and the silence’, and for the first time she empathises with the Númenórean kings. And Aragorn, graced with with the power to choose when to lay down life voluntarily, does so on his own birthday.

Queen Margrethe has relinquished the throne, not life itself. But the timing of her announcement is striking. At New Year we all necessarily think about the passing of time. She abdicated on 14 January, exactly 52 years to the day since she acceded to the throne.

I am not suggesting Queen Margrethe was ruled by Tolkien’s story. But The Lord of the Rings certainly has a deep and lasting impact on its closest readers, not merely as an extraordinarily compelling narrative but also as a moral and intellectual lodestone. And once read, it is never forgotten.

We have never been more aware of the dangers posed by rulers who try to cling to power. Age does not necessarily bring wisdom to them. No doubt some find it harder to contemplate the end of power the closer they get to the end of life.

Donald Trump sought to cling to power and has made clear he would use another presidency to avenge himself against those who thwarted him. Binyamin Netanyahu has ruled with intransigent hawkishness so long that many must find it hard to imagine a different Israel. Vladimir Putin has effectively ruled Russia since 1999, making himself a tyrant and violent imperialist. Ukrainians have called Russia Mordor and demonised its soldiers as orcs (a practice Tolkien would have viewed ambivalently).

Recently, news pundits have been examining the influence of Tolkien’s works on hard-right Italian prime minister Giorgia Meloni. As far as she seeks to invoke his own mythology to promote intolerance and undermine human rights, Tolkien would have loathed her.

But The Lord of the Rings is a book of wisdom that can change lives – and perhaps nations – for the better. A truer measure of his influence may now be seen in what Margrethe of Denmark has done after long reflection.

If you enjoyed this article, please consider supporting my writing and research via Steady (Öffnet in neuem Fenster).