Goblin caves, ancient scripts and Tolkien’s gift for invention

Goblin caves at the North Pole! The Father Christmas letters penned by Tolkien tell us some surprising things about the Arctic. They borrow penguins from Antarctica and feature a polar bear who can speak, write and draw. The North Pole is an actual pole and there’s no sign whatsoever of an ocean under all that ice.

Writing these letters to his children gave Tolkien licence to be wildly counterfactual. This was an old desire that also gave his more serious legendarium a flat earth, an earthly paradise and trees that bore the sun and moon.

But in these gossipy, funny, episodic mini-tales he could freely indulge in absurd unrealities – and freely borrow too – without needing to worry about inner consistencies. If he wanted names for North Polar Bear’s nephews, he could make them Finnish (Paksu and Valkotukka, ‘Fat’ and ‘White-hair’). If he wanted a language for Father Christmas’s elf-secretary, he could just borrow it from Middle-earth Quenya (Mára mesta an ni véla tye ento, ‘Good-bye until I see you next’).

I’ve always been interested in Tolkien’s gift for invention, and it seems appropriate to talk about it now at the time of giving and in the context of the Father Christmas letters.

Several enduring aspects of his inventiveness have become clearer to me over the years. Among them is the urge simply to entertain: dressing up as a berserker, falling downstairs, and many other japes – besides writing, of course. Another is the opportunistic grabbing of ideas, to be used immediately or stored up for later. I was delighted when, researching The Worlds of J.R.R. Tolkien, I realised that he used a 1947 Icelandic eruption as grist for the climactic Mount Doom scenes in The Lord of the Rings.

So here’s a possible trigger for one of the longest and most interesting letters from Father Christmas – the 1932 one, in which North Polar Bear (NPB) discovers secret goblin caves at the North Pole.

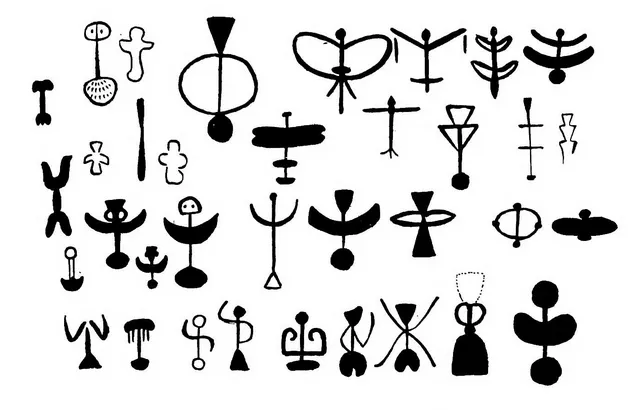

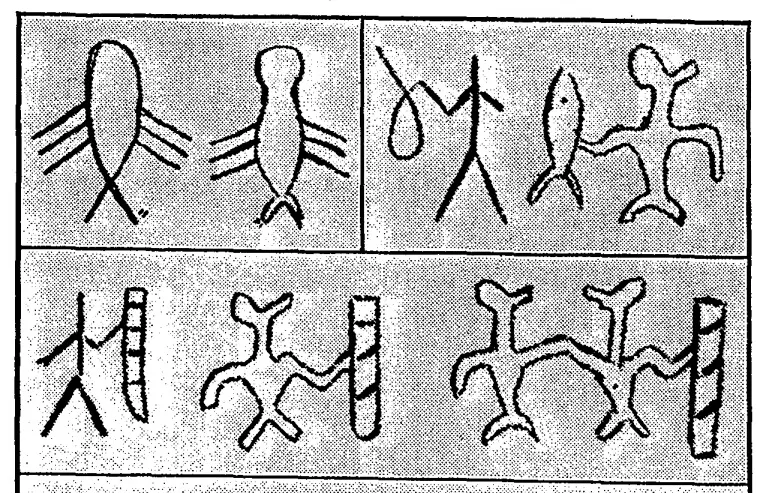

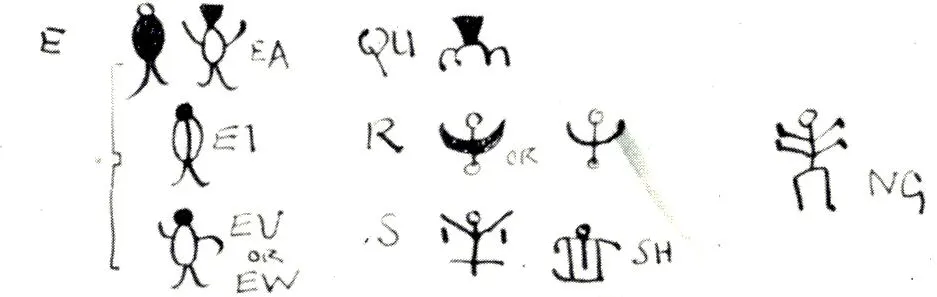

That autumn, The Times reported a new claim that the undeciphered Easter Island rongorongo script was related to the ancient Indus Valley script. The letter included an image with five paired comparisons, including four stylised human shapes. These are reminiscent of figures in the cave art depicted in the 1932 Father Christmas letter – and of the highly figurative ‘goblin alphabet’ concocted from them by NPB.

In fact Christopher Tolkien definitively identified the source for the images: the 1925 edition of M.C. Burkitt’s Prehistory: A Study of Early Cultures in Europe and the Mediterranean Basin (you can browse the first edition (Abre numa nova janela) at Archive.org (Abre numa nova janela), and below is a detail from one of the many plates). That’s why I don’t propose the Times item as a source.

(Abre numa nova janela)

(Abre numa nova janela)Like NPB in the goblin caves, all I’m doing here is exploring. I make no decisive claim. But I do think it plausible that Tolkien needed a spur to pull out his copy of Burkitt seven years after it was published, and the Times letter is something he can hardly have missed. I don’t want to say it’s a dead cert that he saw it; but it’s as near as dammit.

As I say in Worlds (97–8), there’s evidence the Times influenced this particular 1932 Father Christmas letter’s reference to the theory of continental drift. Tolkien was a Times reader. He regularly did the crossword. Turning to the next page in the 21 September issue he would find ‘Letters to the Editor’ and its main item, headlined:

INDIA AND EASTER ISLAND

SIMILARITY OF EARLY SCRIPTS

PROBLEMS OF ORIGIN

The letter (from philologist E. Denison Ross, head of the University of London’s School of Oriental Studies) would entice anyone like Tolkien interested in the history of writing. It reported a new theory about the ancient, undeciphered inscriptions of the Indus Valley – long the subject of controversy but arguably (it said) showing close connections with contemporary Sumeria.

‘M. Guillaume Hevesy, a learned Hungarian resident of Paris, has now made a remarkable discovery,’ wrote Ross. There was a visual crossover – a ‘most astonishing similarity’ – between characters of the Indus script or of Proto-Elamite Susa in Mesopotamia with those of the inscriptions found in Easter Island in the Pacific. Hevesy showed a Paris audience 130 examples of resemblances. Ross’s letter to the Times gives a handful of these (below).

The connection has been dismissed as implausible: several millennia and thousands of miles of land and ocean lie between these civilisations. If Tolkien indeed saw the letter, such thoughts may have crossed his mind too. But it strikes me that there is also a resemblance between the character images accompanying the Times letter and some of the pictures in Burkitt’s Prehistory.

I’m not about to suggest Tolkien theorised a proto-alphabet shared by Easter Island, the Indus Valley and Stone Age Europe. My suggestion is rather less extravagant: that Tolkien saw the letter, remembered Burkitt, and toddled over to his shelves to have another look at the book. Time and space, so challenging to the Hevesy theory, present no obstacle to mine.

Because the Indus and Easter Island images in the Times illustration were (rightly or wrongly) identified as alphabets, my first thought is that there’s a direct line between it and the ‘goblin alphabet’, concocted by North Polar Bear from the images he has discovered in the Arctic cave system. (Below. Hey, someone has created a computer font (Abre numa nova janela) for these!)

But perhaps the Times letter triggered more than just the alphabet.

Tolkien set up the story of the goblin caves well before Christmas, with a November letter from Father Christmas telling the children that NPB had gone missing. So it is even plausible that the Times letter was the further trigger for the entire 1932 Father Christmas letter cave sequence, where the art all derives from Burkitt’s book.

The crossover between this episode and The Hobbit has been recognised previously. Quite what The Hobbit constituted at the time is a moot point: John Rateliff thinks that by early 1933 the story was complete; but Humphrey Carpenter believed it reached no further than the death of Smaug (and was only finished in 1936). Either way, the goblin cave sequence in the Misty Mountains would already be in existence by the time Tolkien wrote the 1932 Father Christmas letter.

Indeed, Tolkien recalled ‘a very big gap’ in composition after the Eagle’s Eyrie, the end of the Misty Mountains adventure – surely one of the two ‘halt[s] in the telling for about a year’ he also recalled (see source note). So that means at least a year passed between the two adventures in goblin caves – Bilbo’s and the North Polar Bear’s. Long enough, perhaps, to reassure the secret Santa impersonator that his children would not spot the telltale similarities. And long enough that here, too, we can imagine Tolkien needed an external prompt to pick up the idea of cave adventures from The Hobbit and weave it into the 1932 Father Christmas letter.

Source note: 1957 radio interview for Carnival of Books with Ruth Harshaw, quoted in Douglas A. Anderson’s Annotated Hobbit, 8; Letters, no. 25, to the editor of the Observer, 20 February 1938.

Help me make time to write and research

New visitors can read about my crowdfunding project here… (Abre numa nova janela)

Gift memberships

It’s a time of giving. It’s also a time of head-scratching for gift ideas and wasteful expense on gift wrap and shipping, presents that may just get put away unused, and so on.

Here’s another idea. Do you know someone who appreciates my work on Tolkien and would like to read more? Did you know you can give them membership of this project?

To see how easy it is, just go to the membership page (Abre numa nova janela) and click on Gift a membership.* You can buy any of the plans, including the new, mid-tier Quickbeam.

As soon as you buy the gift membership, an email goes to the recipient telling them about it and how to access it (but not telling them the price). When the gift expires, it will not auto-renew.

There’s more information here (Abre numa nova janela).

*No, I don’t like gift as a verb either.