02

Brecht’s Library

Recently I got a call from a TV station with a request to appear on a documentary on Bertolt Brecht. Familiar as I am with practically every one of his plays and poems, I have no pretensions to being an expert on the German writer.

‘Why me?’ I asked.

They showed me a photo.

The last one Brecht posed for before he left Berlin…

It must have been 28 February 1933…

Smartly dressed, seated at his desk in front of his bookcase, waiting for the moment of departure.

The reply was, ‘We thought you were the best person to express what he might have felt that moment in that room.’

In front of Brecht's last picture taken just before he left Berlin, in February 1933.

To be honest, I had no idea I would be unable to return to my study when I left home for an indeterminate period. Brecht had left Berlin the day after the Reichstag fire. I was abroad when I heard of the bombing of the Turkish Parliament. It was the witch hunt which followed the attempted coup that prevented me from returning home. Consequently, I had no opportunity to say goodbye to my home, study or books. But it’s not hard to guess what Brecht felt just then:

‘Will I be captured?’

‘What happens to me if I am captured?’

‘What about those I leave behind?’

But mostly, ‘Will I ever be able to go back?’

It’s hard for us all to leave the country we love, the land where we grew up, our home. For us writers, however, there is an additional spiritual wound: being wrenched away from the universe of the language we create in, and the library that feeds our mind…

Writers bereft of their libraries tumble into the void like scientists afflicted by amnesia. In the new city where you now live as an exile, you can buy a new bed, a new armchair and a TV set for your new home; but a library is different. Every book is a memento: you remember the year you bought and read it. Dog-eared pages and underlined passages harbour the sentences that made yesterday’s you into today’s you. A carnation forgotten between the pages still smells of an old love.

The digital generation may carry an entire library on a hard disk; but for our generation, the bookcase is a temple, one where we know by heart which book resides on which shelf. A temple made of paper, built book by book over decades, and crafted a cocoon for its writer…

Worse still, book-haters raid that temple after you’re gone. Callously topple your bookcase and paw your books. Seize those ‘seditious works’ that made you write those ‘horrible ideas’. Sometimes you hear your books were burned in public, like Brecht did, or that they were confiscated and destroyed, like I did…

Exiles may be unable to take their books along, but their books immortalise them. Many a masterpiece was created in exile, a colossal ‘exile library’ of ‘exile literature’, like Pushkin, Dante, Edward Said, Stefan Zweig, Nâzım Hikmet, Herta Müller.

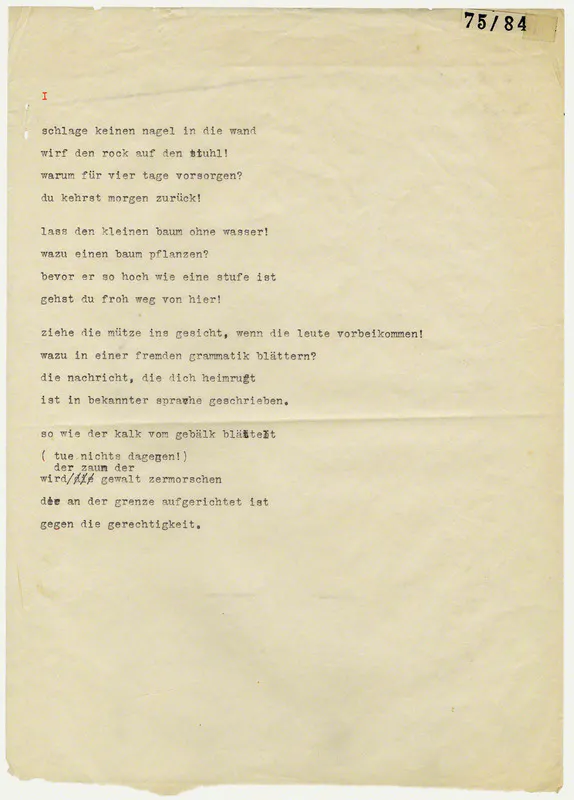

Why bother driving a nail into the wall

Fling your clothes onto the chair instead

Why bother for four days?

You go back tomorrow, after all…

Brecht had been in exile for four years when he wrote the line, ‘Why bother for four days?’ In the fifth year of my exile, I recall that poem every time I drive a nail into the wall.

Exile is a waiting room. Where you long to receive a ‘message calling you back in a familiar language,’ like the poet said. Some, like Nâzım, build a brand-new bookcase in their new home whilst they wait, others, like Brecht, are flung from city to city in all four corners of the earth… ‘Exhausted with waiting for a passport to a different continent.’

Some may call this ‘mobility’, others ‘liberation’…

Akademie der Künste, Berlin, Bertolt-Brecht-Archiv, Nr. 2809 002, © Bertolt-Brecht-Erben / Suhrkamp Verlag

The Brecht House was one of the first places I visited in Berlin… I wandered in that high-ceilinged, bright flat and the room where he breathed his last; I inspected the small desk by the window with his Olivetti on it, the last newspaper he read, which was still standing watch at his bedside, and his library of four thousand volumes.

It had taken him fifteen years to go back to Germany. For him, hope triumphed over reason… Thoughts on the Duration of Exile is the song of that smouldering dream of return…

Never mind watering that young tree

Why plant one more, anyway?

You’ll be gone well before

it grows another handspan…

As I re-read it now, I glance at the sapling I’d planted on the balcony: it’s grown by several handspans…

I wonder how my library is doing.