A mathom on Tolkien’s birthday

One of Tolkien’s gifts to us is the word mathom. It seems a good topic for the Professor’s birthday. So let’s unwrap the word and find out what it has to give us as readers of The Lord of the Rings.

Most readers are likely to meet mathom first in the description of gifts Bilbo gives away on his birthday at the start of The Lord of the Rings. We learn that on their birthdays, delightfully, hobbits give presents rather than receive them. ‘Not, of course, that the birthday-presents were always new; there were one or two old mathoms of forgotten uses that had circulated all around the district.’

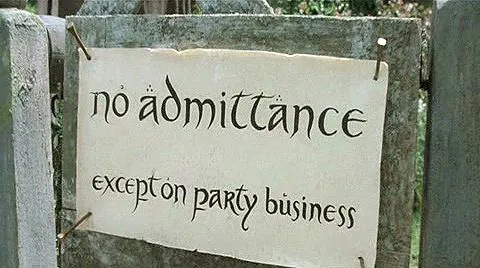

The Prologue has more to say: ‘anything that Hobbits had no immediate use for, but were unwilling to throw away, they called a mathom. Their dwellings were apt to become rather crowded with mathoms, and many of the presents that passed from hand to hand were of that sort.’

Among the objects of no immediate use which hobbits wished to preserve were items of curiosity, of little use to them, and of obscure value. We would call them museum-pieces, and the Shire’s own museum at Michel Delving was called the Mathom-house. One of its holdings, lent by Bilbo, was his mail shirt, given to him from Smaug’s hoard by the dwarves of the Lonely Mountain. In a country where ‘heroes are scarce, … swords … mostly blunt, and axes are used for trees, and shields as cradles or dish-covers’ (The Hobbit, chapter 1), mail shirts too would seem useless. Yet the mail shirt turns out to be worth more than ‘the whole Shire and everything in it’, as Gandalf later reveals.

Mathoms have hidden value, and so does the word mathom.

It’s well known that Tolkien did not invent the word mathom, but borrowed it from Old English maðm (pronounced the same way, to rhyme with fathom). The Anglo-Saxons did not use their word entirely in the hobbit way. To them, a mathom was a ‘precious thing, a treasure, a valuable gift’, as the Oxford English Dictionary defines it. Bosworth and Toller’s Anglo-Saxon Dictionary defines it as ‘A precious or valuable thing (often refers to gifts), a treasure, jewel, ornament.’ The word appears in contexts of much gravity. In Beowulf, for example, it is used for the funeral treasures heaped on the breast of a dead king. Ultimately it comes from an Indo-European word meaning ‘to exchange’ – a fitting origin for a word betokening a gift or other object of value. A maþmus or madmhus (‘mathom-house’) is a treasury.

The first edition of the OED lists the Old English and other forms under the headword madme, the word as recorded in a Middle English version of the Proverbs of Ælfred, written around the year 1250. That’s the entry’s most recent citation.

However, the third edition transfers all this to the headword mathom, because by the time this edition was compiled, Tolkien had successfully revived the word and given it currency in the wider English language. The OED defines a new, Tolkienien sense for this revived form of the word: ‘a trinket, a piece of bric-a-brac’. It furnishes a couple of citations, one from American science-fiction writer James Blish in 1970 and another from a magazine, Byte, in 1998: ‘A storage company where I keep a bunch of mathoms – stuff I can't quite bring myself to throw away.’

OED editors Peter Gilliver, Jeremy Marshall and Edmund Weiner consider some of this in The Ring of Words: Tolkien and the Oxford English Dictionary – a book I wholeheartedly recommend. They comment: ‘This fits the cultural framework of Tolkien’s story very well. The warriors of Rohan, whose society bears many resemblances to that of the Anglo-Saxons, share a number of words with the hobbits, mathom included (we are told in the Prologue); but the latter are peace-loving rather than heroic, middle-class rather than aristocratic. The adaptation of the word into a worn-down modern English form with a domestic sense mirrors the cultural status of the Shire with gentle humour.’

Tom Shippey assumes that mathom entered The Lord of the Rings when the opening chapter was first written. ‘It seems that Tolkien had not decided early on how funny the hobbits were to be. Some of the parodic element of The Hobbit persists for a couple of chapters: “eleventy-first”, “tweens”, “mathoms”, etc.’ Shippey seems not to like this kind of humour.

However, for all his tremendous insights into Tolkien, Shippey is mistaken about when mathom entered The Lord of the Rings and overlooks the deeper significance of the word.

After Shippey wrote these comments in The Road to Middle-earth, Christopher Tolkien published the composition history of The Lord of the Rings. The idea that hobbits give presents on their own birthdays appeared in an early version of ‘A Long-Expected Party’ (Return of the Shadow, 21). It’s an essential accompaniment to the essential plot idea that Bilbo could use his birthday to give the Ring to Frodo. But there was no mention of mathoms in these early texts. Nor did ‘Mathom-house’ appear in the conversation about Bilbo’s mithril coat in Moria, where ‘Michel Delving Museum’ appears instead (Treason of Isengard, 185).

In fact Tolkien introduced the word mathom to hobbit vocabulary very late in the composition of The Lord of the Rings, in what became Appendix F ‘On Languages’: ‘The curious Hobbit-word mathom, which has been mentioned, is clearly the same as the word máthum used in Rohan for a “treasure” or a “rich gift”. The horn given at parting to Meriadoc by the Lady Éowyn was precisely a máthum’ (Peoples of Middle-earth, 39). This was written before summer 1950, but not long before. And he introduced mathom into the Prologue too, around the time he wrote ‘The Scouring of the Shire’ in 1948 (Peoples of Middle-earth, 8).

So the word mathom entered The Lord of the Rings much later in its long composition than Shippey suggests, and I would argue that the thought Tolkien put into it was much more profound.

Yes, as Gilliver, Marshall and Weiner say, there is gentle humour in the way the hobbits have adapted a weighty ancient word to mean something you keep simply because you don’t want to throw it away. But the hobbits’ attitude to material wealth is involved with their attitude to power, an essential part of the theme of The Lord of the Rings. They are haphazardly greedy for wealth (at least Sancho Proudfoot is, excavating in Bilbo’s pantry in hope of discovering hidden treasures). But they are largely content if their truer appetite is satisfied – their desire for plenty of good food. A mithril shirt worth more than the Shire gets relegated to the Mathom-house as a mere curio; like a sword or shield, it has no practical use. Hobbits are generally fortunate enough not to have to defend their land with arms, and they have no ambitions to raid or invade other lands.

At the opposite extreme to hobbits with their free and casual circulation of gifts, Sauron is what the Anglo-Saxons (or the Rohirrim) would have called a máðum-gifa, ‘treasure-giver’. Treasure-giving was the glue of Germanic society: a lord would reward his retainers with treasures, particularly rings as a form of easily portable and visible wealth. They would be bound to him in fealty. As Lord of the Rings, Sauron uses his gifts of treasure to bind his servant Ringwraiths into a particularly sinister fealty, a compelled service filled with dire obligations.

The Ruling Ring comes to Gollum thanks to three acts of violence and robbery – Isildur’s amputation of Sauron’s ring finger, the Orcs’ slaying of Isildur in the Gladden Fields, and Sméagol’s own murder of Déagol. But he insists it was his ‘birthday present’ from Déagol, or ought to have been. Evidently, the Stoors of the Vale of Anduin customarily received presents on their birthdays, unlike the hobbits of the later and more enlightened Shire. It is Gollum’s ‘Precious’ – and I would lay odds that when Tolkien introduced the word mathom to his story, he had in mind the Old English sense recorded in the standard Anglo-Saxon dictionary, Bosworth and Toller’s: ‘A precious or valuable thing (often refers to gifts), a treasure, jewel, ornament.’ The Ring is Gollum’s mathom. It is something Gollum keeps because he is literally unable to throw it away.

Bilbo receives it by a providential accident – it slips from Gollum’s finger in the nick of time for him to find it in the tunnels of the Misty Mountains. When Bilbo later becomes the first Ring-bearer to willingly give the Ring away, on his own birthday, he makes it a mathom in the normal Shire-hobbit sense. He gives it to Frodo by defeating its malign power to foment possessiveness.

In turn, that act of giving is Bilbo’s gift to the world, for without it Frodo could not undertake the quest to destroy the Ring.

I hope these thoughts are also a fit gift to my readers on this 133rd anniversary of Tolkien’s birth.

Happy birthday, Professor!

*****

These thoughts remind me to remind you that you can give gift memberships for my Steady project, if you know someone else who would like to support my research and writing on Tolkien.

To see how easy it is, just go to the membership page (Opens in a new window) and click on Gift a membership.* You can buy any of the plans, including the new, mid-tier Quickbeam.

As soon as you buy the gift membership, an email goes to the recipient telling them about it and how to access it (but not telling them the price). When the gift expires, it will not auto-renew.

There’s more information here (Opens in a new window).