Tolkien Reading Day and the machine war against imagination

Every year on 25 March we celebrate Tolkien Reading Day. It marks the date in The Lord of the Rings when the Ruling Ring is destroyed – the One Ring to bring them all and in the darkness bind them. As a celebration of a single author’s extraordinary imagination, it’s also a celebration of the human imagination itself.

Today also happens to be the day when I discover just how many of Tolkien’s works have allegedly been used by Meta, without permission, to train artificial intelligence. According to The Guardian (Opens in a new window), Meta boss Mark Zuckerberg gave permission for its AI software to ‘scrape’ a vast database from Russia containing more than 7.5 million books in multiple languages. The Atlantic (Opens in a new window) offers a list of what’s in the database. A lot of Tolkien and a great deal of work by other authors – even including me.

The word scraped, evoking a process both painful and mechanical, makes it sound as if these products of our countless individual minds were just some kind of mould.

This development would have horrified Tolkien and ought to horrify anyone who admires his work.

Though the Ruling Ring is portrayed as magical, it is also a ruthlessly simple machine – a lever that gives a small addition of power to the weak but a massive boost to the powerful. Tolkien wrote that The Lord of the Rings was about ‘the desire for Power, for making the will more quickly effective, – and so to the Machine (or Magic). By the last I intend all use of external plans or devices (apparatus) instead of development of the inherent inner powers or talents – or even the use of these talents with the corrupted motive of dominating: bulldozing the real world, or coercing other wills.’

Not only would any action of such large-scale ‘scraping’ be a bulldozing breach of copyright on a scale to beggar belief. It would also be a declaration of war against what it means to be human.

The principle of copyright is so simple that even Mark Zuckerberg must understand it. His own company’s lawyers must spend vast amounts of time defending intellectual copyrights he has established. He certainly doesn’t want the software secrets or datasets behind Facebook, Instagram and WhatsApp to be made available to rivals.

And make no mistake, AI is a rival to human intelligence. I’m willing to accept that its vast data-crunching capacities may benefit science and medicine (though I’ll bet that for every miracle cure it produces there’ll also be a murderous new weapon). But AI is a cuckoo in the human nest, and like a cuckoo it will progressively outgrow and destroy everything that competes for its food.

This is particularly grim news for the creative arts. Very few authors make fortunes like Tolkien has (mostly posthumously). But AI will produce faster and more cheaply. It will hit marketing targets more effectively. It will cheapen the arts and steal audiences. Authors will be forced to give up – or starve. In the world that’s coming, Tolkien might have written some of his stories, but he would have been out-competed, unpublished.

The AI problem goes far deeper than copyright, anyway.

Making stories, poetry, drama – these are all vitally human activities. Each may express the imagination of a human mind engaged with the other humans, or with nature or (yes) technology.

The products of AI can never do that. However convincing they seem, they are mimics, chameleons, ciphers. They are as hollow and two-dimensional as the fake building facades on a film set.

And the damage will worsen exponentially. AI will not only recycle from original human sources it has ‘scraped’. Increasingly, it will recycle from the products of AI mimicry. Cliché will pile on cliché. If literature helps us see our world, AI will obscure our vision.

(That, maybe, is Zuckerberg’s dream, when we can all live happily in his metaverse.)

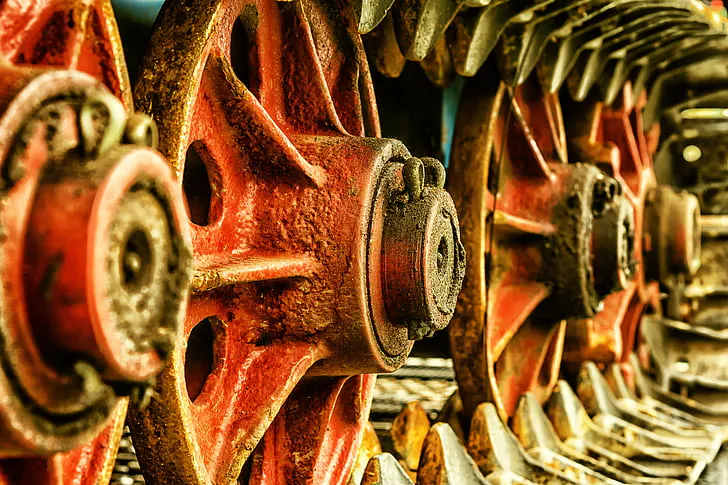

The Enemy in Tolkien’s world is sheer materialism, blind to all value except wealth and power. To Saruman, with his ‘mind of metal and wheels’, a tree is never a thing of beauty or unique individuality; it is mere timber or even just a obstacle to be removed. To Sauron, the Elven rings that give power to heal and sustain are objects to covet. To Morgoth, the Elves and Ents are creatures to conquer or destroy – or to corrupt into a mimickry of themselves, producing the miswrought monsters that are Orcs and Trolls.

No doubt Saruman – with his inability to distinguish timber from everything else that a tree is – would have seen no difference between human thought and artificial intelligence. They look the same, so they’re interchangeable, right? That seems to be the view of many scientists who think we’re on the brink of creating a mind-like Artificial General Intelligence.

But let’s be clear. We are far from understanding how the human mind works. So how can we know if AI can truly replicate it? We know what consciousness is – because we feel it. By extension and by empathy, we can recognise it in other living creatures. There is no evidence that machines, however clever, will ever gain consciousness, with its capacity for joy and pain, love and hate.

AI can scrape away at literature and steal its clothes, but it can never be part of the ages-old miracle that happens when one human tells a story to another. When we reach the point of believing that it does, we will be lost in a hall of mirrors.

If you enjoyed this post and would like to support my ongoing research and writing on Tolkien, please consider giving me your vital support via my Steady crowdfunding page (Opens in a new window).