Where did Tolkien’s Silmarillion hero Beren get his name?

Beren is a name etched in the memories of Middle-earth fans. And it is literally carved beneath Tolkien’s own name on his Oxford gravestone. There was never a clearer statement of an author identifying with a character of his creation. But what does the name Beren mean?

The mythology began as a home for Tolkien’s invented Elvish languages. So you might expect him to record a meaning for the name he gave to the hero of the central story of The Silmarillion. From a lifetime’s work, we have evidence of just one clear explanation.

Tolkien’s Etymologies, a 1937 lexicon of Elvish word-roots and their derivatives, glosses beren as ‘bold’, related to a verb bertho meaning ‘to dare’.[1] (Öffnet in neuem Fenster) Very fitting for the hero who goes to the heart of the enemy’s realm and cuts a holy jewel from his iron crown.

However, Tolkien is unlikely to have had ‘bold’ in mind when he first coined the name in 1917. His Elvish lexicons from that earliest period of his invention have nothing similar to it. And anyway, one motivation of the Etymologies was to provide philologically cast-iron derivations for some his earliest names, which he had come to see as slapdash.

Appropriately, one example of this is the name Lúthien, which Tolkien gave in the 1920s to Beren’s elven lover (previously just called Tinúviel). Tolkien had earlier intended Lúthien to mean ‘friend’, and his plot notes show he tried it as a name to a succession of male characters. But the Etymologies derives Lúthien from a root meaning ‘magic, enchantment’ and translates it as ‘enchantress’. By the time he had it carved beneath his wife Edith’s name on her gravestone in 1972, he had decided it meant ‘daughter of flowers’.[2] (Öffnet in neuem Fenster)

So beren ‘bold’ in 1937 may well tell us nothing about the meaning of (or motive for) Beren when Tolkien first used the name in 1917.

Now a chance encounter with a book in the Bodleian Library has led me to a plausible and intriguing possibility.

The Mackerras Reading Room in the Weston Library is where you go these days if you want to read Tolkien’s academic manuscripts. You must fill in a request to see particular manuscripts, then go to the issue desk, where a librarian will fetch your next item from behind the scenes. While I wait, I’m always drawn to the books on the nearest open shelves – titles on music or on place-names.

On this occasion I spotted The Place-names of Oxfordshire, their origin and development, by Henry Alexander, and casually flipped it open. Near the start of the glossary of names, these words arrested my eye:

Beren’s Hill (near Ipsden).

Tolkien joined the English Place-name Society on its foundation in 1923. It’s hard to imagine him missing this earlier, local study, which would have been in bookshops and on library shelves for most of his undergraduate years at Oxford. When Alexander’s book appeared in 1912, the Modern Language Review called it ‘one of the most scholarly studies yet published in the investigation of English place-names’.[3] (Öffnet in neuem Fenster)

But the reference to Ipsden also grabbed my attention. It may well have grabbed the young Tolkien’s too – for entirely personal reasons. From my own previous research I knew that he had a friend and confidante from an important family there.

This was Father Vincent Reade, a colleague of Tolkien’s guardian at the Birmingham Oratory, the Catholic priestly community and church. Fr Vincent was the great-nephew of author Sir Charles Reade (1814–1884), famous in his day for The Cloister and the Hearth and many other novels. Though Fr Vincent himself was not born at Ipsden House, generations of the Reade family had been, ever since the 16th century (and continued to be after him). There’s a (Öffnet in neuem Fenster)small image of him here (Öffnet in neuem Fenster).

He had a close bond with Tolkien. When Fr Vincent went to serve mass at a church in Cornwall for a few weeks in August 1914, Tolkien went with him and they hiked all over the Lizard Peninsula. In a letter to Edith that November, Tolkien mentions ‘performing my duty to Fr Vincent’s mother’ by visiting her at her home in north Oxford.[4] (Öffnet in neuem Fenster) After enlisting for military service in July 1915, he sent Fr Vincent long complaining letters about the oppressiveness of army training and camp life.

Beren first stumbled into story in 1917 as a dazed wanderer who sees the Elf-princess Tinúviel – later Lúthien Tinúviel – dancing among hemlock flowers and falls fatefully in love. Tolkien took the encounter from a moment in real life – but not from anywhere near Ipsden. It was in a Yorkshire wood at or near Roos that his wife Edith danced for him among the tall white flowers, when he was recovering from the Battle of the Somme. In Tolkien and the Great War I try to identify the real wood.

Had Fr Vincent talked to the young Tolkien about Beren’s Hill and its curious name? His great-uncle, Edward Anderdon Reade, had retired to Ipsden after service in India and had there taken up antiquarian research into the area, writing essays on local landscape (he gave them to the Bodleian Library).[5] (Öffnet in neuem Fenster) Fr Vincent himself was a man of ‘immense erudition’, according to Oratory records.

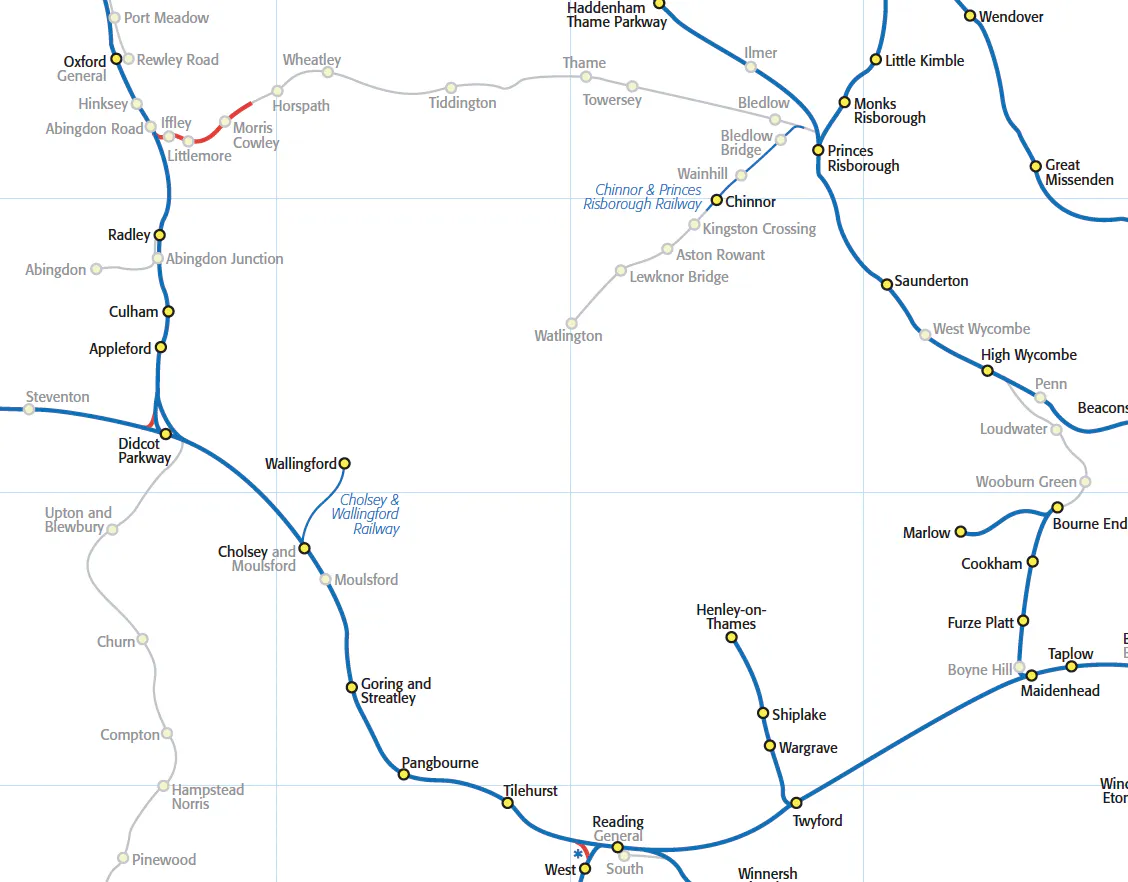

Had Tolkien actually visited Ipsden? He certainly cycled from Oxford to the White Horse of Uffington, which is an even longer ride. Perhaps he rode to Ipsden with King Edward’s Horse, the territorial cavalry regiment he joined as an undergraduate. It was a popular meeting place for hunts, at any rate. It was also accessible on foot from one of the nearby railway stations – Cholsey on the main Oxford-to-Reading line, or Wallingford on its own branch line (the nearest stop), or Watlington on the old branch line from Princes Risborough. The image below is from a historical atlas of railways (Öffnet in neuem Fenster) (with the lines that are now disused marked in grey).

(Öffnet in neuem Fenster)

(Öffnet in neuem Fenster)And besides the personal connection via Fr Vincent, Beren’s Hill is on a spur of the imposing Chiltern Hills, near the Goring gap and looking towards the nearby Berkshire Downs. It would be a natural attraction for someone like Tolkien or his best friend at Oxford, G.B. Smith, who was apparently a demon for country walks.

You can find Berins Hill, as Beren’s Hill is now officially spelt, on the map just east of Ipsden. Above is a small section of the six-inch Ordnance Survey map (Öffnet in neuem Fenster) from the era we’re talking about. The photographs in the current post are from a quick drive there last September – my first visit and my only one so far. (You can see various others at the Geograph website (Öffnet in neuem Fenster).)

According to Murray’s 1894 Handbook to Oxfordshire (Öffnet in neuem Fenster), a religious mission had once been sent out to Ipsden by Birinus, first bishop of Dorchester on Thames, and Berens Hill (so spelt) derives from ‘Birinus’ Hill’.

In his guide to Oxfordshire place-names, Henry Alexander cites Murray’s claim but calls the idea ‘probably an etymological figment’ (Öffnet in neuem Fenster). He means that after the true origin of Beren’s Hill fell into obscurity, it was incorrectly associated with the name of St Birinus, the Frankish missionary who had converted the king of Wessex in 635.

More specifically, Margaret Gelling brands it an ‘antiquarian association’. She means that the supposed link with Birinus was a guess made by antiquaries – historians who worked before in philology and archaeology in the 19th and 20th centuries brought critical rigour to such research. She derives Berins Hill from Old English byrgen, as you can see in a passage about the perils of place-name studies quoted in this (rather sniffy) blog post (Öffnet in neuem Fenster). The English Place-Name Society follows suit in its Survey of English Place-Names (Öffnet in neuem Fenster).

Alexander’s much earlier entry for Beren’s Hill doesn’t give a clear alternative to Birinus as the origin of the name. But in an appendix on ‘personal names as first elements’ has this speculative entry:

Beorn (Beren’s Hill?)

Alexander does note that a related form, Beorna, probably appears (much reduced) in the modern place-name of Bicester, north of Oxford.

In fact, before Tolkien gave the name Beren to the hero of the Tale of Tinúviel, he first fleetingly calleda completely different man Beren or possibly Berin. He is not a hero at all – rather the opposite. This is shown by a couple of isolated story notes, earlier than the Tale of Tinúviel but relating to Eriol, the Germanic mariner who hears the tales of the Elves in the Book of Lost Tales, the earliest form of The Silmarillion. They are published in Parma Eldalamberon, an essential journal for people seriously interested in the invented languages (and I would say, for people seriously interested in how Tolkien created Middle-earth).

All the notes say about this earlier Beren/Berin is that he killed or ‘destroyed’ Eriol’s father, a lord in eastern lands somewhere in Europe. But the notes give Beren/Berin other names too: Beorn, which we know is Old English for ‘warrior’ but once meant ‘bear’; and Bernus, which may be Tolkien’s idea of what this would be in Gothic (reconstructed *baírnus).[6] (Öffnet in neuem Fenster)

Perhaps in these early notes Tolkien meant the Old English and Gothic forms merely as soundalikes for the Elvish. Perhaps, on the other hand, he meant them as relations of Elvish Beren or Berin – developing from a common ancestor. This should not be surprising, because at this point (unlike in The Lord of the Rings) Tolkien imagined a relatively brief period between the time of the Elves and historic human times. The Lonely Isle of the Elves was meant to be Britain/England.

Where does all this leave us?

Tolkien is likely to have known of Beren’s Hill; indeed, he is unlikely not to have known of it. Probably he knew it personally via Vincent Reade, and perhaps he visited the hill himself. Together with this, it is even more likely that he knew of the disputed and doubtful etymology via Henry Alexander.

A philological enigma could be enough to set off Tolkien’s creative imagination. That’s how the Old English name Éarendel led to him inventing his first Middle-earth hero, the star mariner Eärendel, in September 1914.

The enigma of Beren’s Hill does not seem to have sparked a story in itself. Or if it did – in the sense of a story to explain the place-name – not a word of it has survived, and it went the way of other ephemeral ideas that he jotted down in his notes for the Book of Lost Tales, like Sirion as the name for England’s River Trent, or for the River Severn, or for the Rhine.

There’s so much we cannot know about this time of flux when the first ideas of the mythology were being laid down. But I think it is a reasonable guess that the name Beren pleased Tolkien so much that he adopted it into Elvish, and its theoretical connection with the Old English word for ‘bear, warrior’ was vital.

First, probably early in 1917, the name embodied the idea of a fearsome or even feral enemy, the Beren or Berin who ‘destroyed’ Eriol’s father. Later that year, Tolkien came to writing a story celebrating his love for Edith and her part in reviving him from war horrors. So he took the name instead – now as a mark of raw courage – for the hero who steals the Silmaril.

I spoke briefly about this discovery in an Oxford talk titled ‘“An Entirely Vain and False Approach”: Literary Biography and why Tolkien was wrong about it.’ This was at a conference last September marking the 50th anniversary of his death. I had intended to expand on this little gem about Beren in a blog post before the film of that talk (Öffnet in neuem Fenster) went live. In the end, the video came out last week without warning.

Thanks go to Maria Artamonova for drawing my attention to the blog post about Margaret Gelling and byrgen. Also to David Haden, whose recent blog post (Öffnet in neuem Fenster) about my Beren’s Hill discovery alerted me to J.E. Field’s St Berin: The Apostle of Wessex (Öffnet in neuem Fenster), 1902). I particularly appreciate his long quote about ‘Berin’s Hill’ (which is not, however, from Methuen’s 1906 Little Guide, Oxfordshire, but from the Field book).

[1] (Öffnet in neuem Fenster)The Lost Road and Other Writings, p. 352.

[2] (Öffnet in neuem Fenster)Lost Road, p. 370; Parma Eldalamberon no. 17, p. 11. On the origin and important implications of Lúthien ‘friend’, I say more in The Worlds of J.R.R. Tolkien, p. 56.

[3] (Öffnet in neuem Fenster) Review by W.J. Sedgefield in The Modern Language Review, Vol. 8, No. 2 (April 1913), 243. It wasn’t superseded until Margaret Gelling’s magnificent two-volume Place-names of Oxfordshire appeared in 1953–54.

[4] (Öffnet in neuem Fenster) Catherine McIlwaine, Tolkien: Maker of Middle-earth, 154–5.

[5] (Öffnet in neuem Fenster)Oxford Dictionary of National Biography.

[6] (Öffnet in neuem Fenster) ‘Brief texts and fragments from the Lost Tales manuscripts’, Parma Eldalamberon no. 15, p. 16.