Towards a more dynamic typology of regions for Cohesion Policy

March 2024

Cohesion Policy is the cornerstone of the EU’s efforts to promote economic, social, and territorial cohesion by reducing disparities between regions. Since its start, it has evolved to address the changing dynamics and challenges facing EU regions and citizens. However, as the EU faces new economic, environmental, and social transitions, Cohesion Policy needs to develop more dynamic typologies of regions, going beyond the categorisation of less developed, transition and more developed regions, based on regional GDP per capita.

The report of the group of high-level specialists on the future of Cohesion Policy (Opens in a new window), makes an interesting proposal for a more dynamic typology of regions. This is based on recent research on development traps, and the need to pay more attention to the nature of challenges and the responses needed in every region.

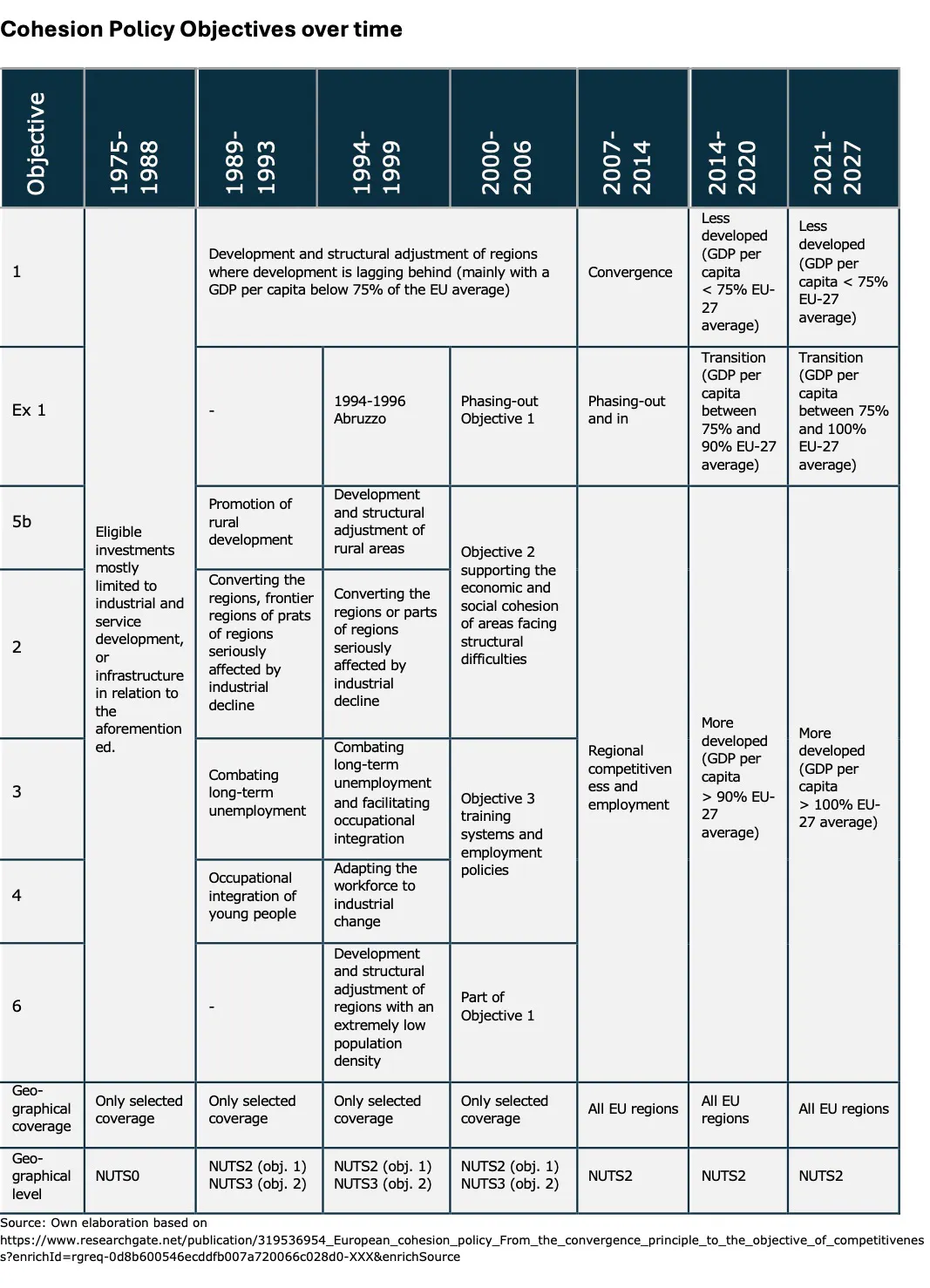

Cohesion Policy regional typologies 1975-2027

Between 1975 and 2006, the emphasis of Cohesion Policy was on investments and growth in less developed areas. This steadily included more focus on areas affected by industrial decline, adapting to industrial change, rural development, sparsely populated areas, etc. Still, for the first 30 years of Cohesion Policy, there were limited areas eligible for support and these did not cover all parts of the Union.

As of 2007, all regions in the EU became eligible for Cohesion Policy. This was reflected by the introduction of the ‘convergence’ and ‘regional competitiveness and employment’ objectives (2007-2013). Since the 2014-2020 period, Cohesion Policy has worked with ‘less developed’, ‘transition’ and ‘more developed’ regions. At the same time the granularity used to define eligible regions was reduced to NUTS2.

The definition of these regions and the financial allocation of EU Cohesion Policy is based on GDP, as visible in the definition of less developed, transitions and more developed regions and their co-financing rates. For the 2021-2027 period, less developed regions are defined as those having less than 75% of the EU-27 average GDP per capita. Transitions regions have between 75% and 100% of the EU-27 average GDP per capita. More developed regions have more than that.

Need to go beyond GDP

GDP is certainly an imperfect indicator and the focus of policy making on GDP has been criticised for many years. This concerns both general economic policies and Cohesion Policy in particular.

To read this post you'll need to become a member. Members help us fund our work to ensure we can stick around long-term.

See our plans (Opens in a new window)

Already a member? Log in (Opens in a new window)