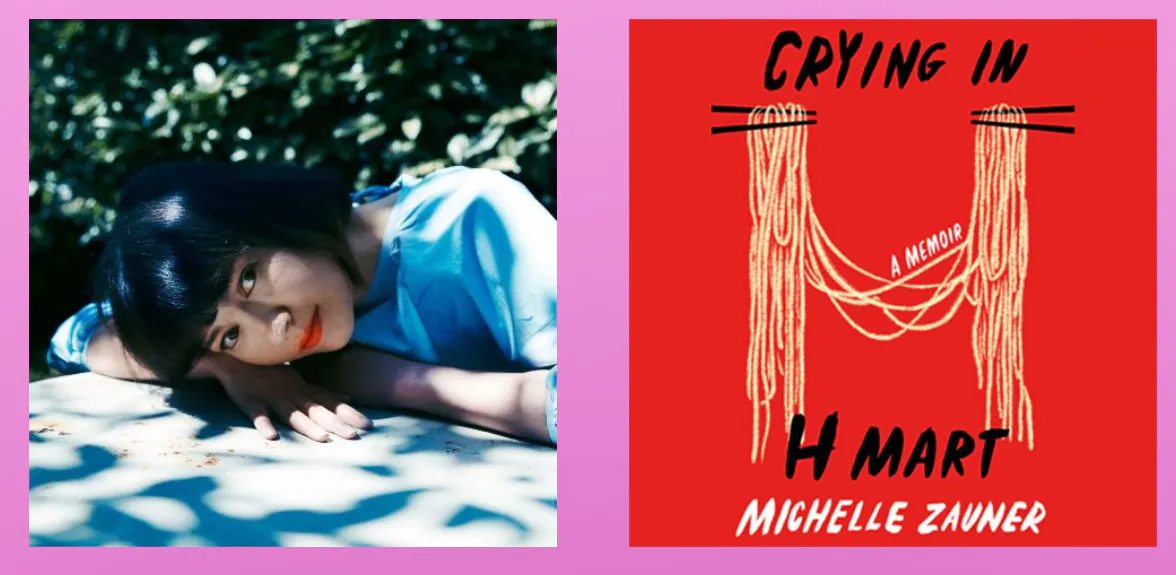

Passage That Changed Me: Helen Ganya (Opens in a new window) on Michelle Zauner’s Crying in H Mart (Opens in a new window)

How Crying in H Mart helped me understand my Thai family’s love language

"I remember these things clearly because that was how my mother loved you, not through white lies and constant verbal affirmation, but in subtle observations of what brought you joy, pocketed away to make you feel comforted and cared for without even realising it. She remembered if you liked stews with extra broth, if you were sensitive to spice, if you hated tomatoes, if you didn't eat seafood, if you had a large appetite.”

Michelle Zauner, Crying in H Mart

I read Crying in H Mart last year. It coincided with my desire (which I’ve felt since the pandemic) to connect more with other ESEA artists and their work; in finding similarities – even in the tiniest of ways – in other people’s experiences and expressions. Reading this passage still sticks with me in that way. I have always struggled with the Thai side of my heritage, of trying to understand my mother's love and where I fit in – both in her eyes and also in wider Thai culture.

This passage completely changed my perspective on what I thought I lacked. The expression of love from my mum has always been through food and specifically remembering what I like to eat and how I like to eat it. When she comes to visit, she regularly brings all the ingredients to make meals in my kitchen. A tom yam with just the right spicy and sour blend to feel revitalised, even during the height of summer. Or a refreshing yum woon sen (with plenty of pickled garlic), which never fails to bring up the memory of sitting on a sandy beach in Hua Hin, eating that dish with my grandmother. My mum will bulk up my freezer with the classic green, red and yellow curries, always giving me something to fall back on for when I feel uninspired or just don’t have the time to cook. This is how she knows who I am – my Thainess inherent and most obvious in the food we share together.

However, I was afraid that she would be the only one to know me in this way.

I grew up in Singapore and spent my long school summers in Thailand with my mum. We mainly went to the north-east province Udon Thani to visit my grandparents and extended family members and then to Bangkok to visit my aunt and to make multiple temple trips. I returned to Thailand earlier this year as part of a research placement in Bangkok. It was the first time I had been back since 2014. It was also the first trip I did without my mum and since the loss of my grandmother whose presence held many generations and extensions of the family together.

As the plane landed, I saw the first pagoda and wept. I immediately knew my grandmother wasn’t here and I suddenly felt afraid to reconnect with my family. After so much loss and many schisms, where was my place now? How would people know or be convinced of my Thainess without the matriarchal line here to protect me?

After so many years of not seeing my relatives, I knew I had to be the one to suggest meeting up – for lunch of course. As I entered the restaurant, I was taken by how everyone felt exactly the same. Other than the obvious absence of my grandmother, it really did feel like no time had passed. All the food I loved was ordered, no questions asked. They remembered it all.

My month in Thailand was a reinvigoration of the cuisine alongside a reconnection with family. My cousin would show up in a van out of the blue with tupperwares of dishes she’d cooked for me, not even stopping for small talk. She would take me to different markets and find for me desserts she really wanted me to try like thong muan sot and roti sai mai. My aunt made sure when we visited the historical capital Ayutthaya, that we went to the best lunch spot for the most delicious kuay teow reua.

In my spare time, I read up on the history of Thai cuisine, and most specifically Maria Guyomar de Pinha – a mixed race Thai woman in the Ayutthaya period who created so many of the auspicious desserts that Thais know and love today. She became my muse on the trip. A mixed race woman in a historic Thai period linked to food seemed so niche to me (though I’m sure it probably wasn’t), but it reminded me that Thainess isn’t detached from the outside world.

Just because my language skills aren’t great or that most Thais won’t recognise my Thainess, it does not mean I cannot stake a claim to being Thai. I finally accepted that much of my identity and sense of belonging was in the food I craved and ate, and I realised that this was the way my relatives acknowledged this, too.

"Things I used to find annoying as a child – like my aunt piling food onto my plate without me asking – I now see as acts of love, care and acceptance from them all"

Michelle Zauner’s passage set me on a journey to realising that this went far beyond the relationship with my mother and that it extended to the rest of my family. This fact made me feel less lonely. Things I used to find annoying as a child – like my aunt piling food onto my plate without me asking – I now see as acts of love, care and acceptance from them all.