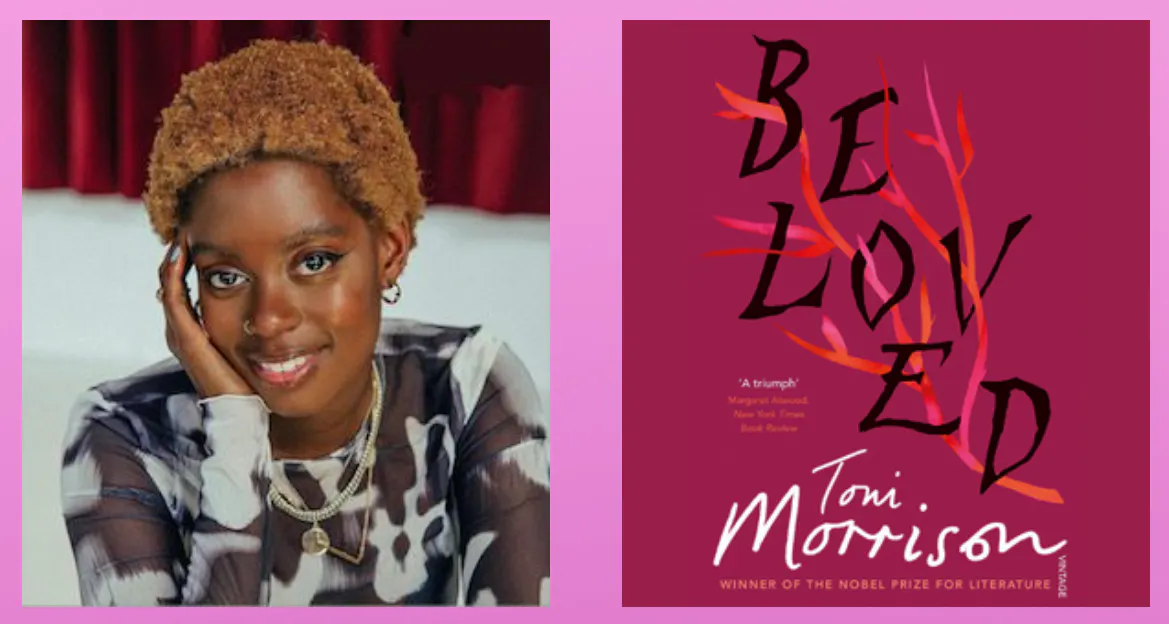

Passage That Changed Me: Nali Simukulwa, Toni Morrison’s Beloved (Opens in a new window)

How Toni Morrison helped me in balancing my sexuality and faith

“In this here place, we flesh; flesh that dances on bare feet in grass. Love it hard. Yonder they do not love your flesh.”

Toni Morrison, Beloved

Even in the rainy season, Lusaka is warm. Cloying humidity hangs still and the atmosphere seems to swell indoors, the room pressing its skin against yours until you merge; your sweat becomes a second wallpaper. On days like that, shade is the goal. Days before Christmas, I stood beneath a canopy alongside the congregation as a pastor delivered his sermon, his pulpit having been relocated outside, above us hanging sheets blocked out the sun.

I listened to the Lord’s word as he preached. I didn’t hear it though – my mind was on the Matalan shawl my mum had forced me to wear. “Cover your shoulders,” she instructed me. 14 years old and indignant, I spent the service silently sulking: the highest penalty I could dish out against an institution I viewed as a threat to my burgeoning feminist principles. Faith felt so far away from me.

It wasn’t always this way. At my Catholic primary school, Wednesday mornings saw the hall, ordinarily reserved for P.E. lessons and squashed butties, come alive. Row by row the room filled with chubby-cheeked babies in oversized sweatshirts to almost-teenagers taking pride of place on wooden benches. Together we sang out hymns, stamping our feet and sharing smiles as we competed to see who could clap louder during ‘Shine Jesus Shine’. This was religion to me – singing with friends and feeling unbounded joy.

"I turned away from the church, trying to get one step ahead of the rejection I so badly feared"

Discovering my queerness changed things. Ashamed and scared, I turned away from the church, trying to get one step ahead of the rejection I so badly feared. I believed the groups who used religion to justify their hate and Christianity became the target for my anger at the world’s injustice. So the church became a place where I felt stifled and afraid to be myself.

A university open day led me to Toni Morrison’s Beloved and I was enthralled. Intense from its first word and bathed in the spirit of Baby Suggs, holy, the novel’s spectral mother, the story touched me instantly. Writing with a viscerally truthful absurdity, Morrison leaves no room for doubt as the narrative sucks you into a world where suffering is inevitable and reprieve is found in the supernatural. Morrison’s depiction of Baby Suggs and her enduring legacy helped me understand the holy spirit in a way I hadn’t before.

Armed with a lifetime of wisdom borne out of hardship, Baby Suggs becomes her community’s “unchurched preacher”, giving her reluctant parish licence to live outside the constraints of perfection. She doesn’t demand endless forgiveness from those to whom the world is rarely forgiving, she simply lets them exist in their pain, their anguish and their joy. Baby Suggs offers an embodied religion, one that recognises its followers’ worldly struggles and holds space for them to heal.

Armed with a lifetime of wisdom borne out of hardship, Baby Suggs becomes her community’s “unchurched preacher”, giving her reluctant parish licence to live outside the constraints of perfection. She doesn’t demand endless forgiveness from those to whom the world is rarely forgiving, she simply lets them exist in their pain, their anguish and their joy. Baby Suggs offers an embodied religion, one that recognises its followers’ worldly struggles and holds space for them to heal.

“In this here place, we flesh; flesh that dances on bare feet in grass. Love it hard. Yonder they do not love your flesh.”

Toni Morrison, Beloved

Baby Suggs calls out to her congregation, I read those words and part of me came undone.

"I read those words and part of me came undone"

Far from the vision of a punitive, judgemental faith I had harboured in my spiritual exile, through Baby Suggs, Toni Morrison taught me that faith, above all, can be understanding. The God I began to imagine didn’t demand perfection, they didn’t scorn me for my love or ask me to repent for what I am not sorry for. I began to believe once more that religion was a place of joy; that I could come exactly as I was and be welcomed with open arms.

"Two facets of my identity that for so long felt opposed came together in a moment that felt rapturous"

At a queer rave weeks ago the DJ turned to the mic, “I want to see hands in the air as we praise for this next one,” he said as a gospel song began to play and the dancefloor flooded with coloured light. Around me people clapped, beaming smiles on their faces as they stamped their feet. Two facets of my identity that for so long felt opposed came together in a moment that felt rapturous.

I remembered Baby Suggs and her long suffering congregation as I danced and smiled, the warm glow of the wine I had drunk unfurling in my chest. “Flesh that dances,” rang in my ears as the music pulsated around the room. A man with a blinking tooth gem grabbed my hand, and held it as he swayed, his rolling muscles contained beneath a glittering mesh top. He spun me around and as the world whizzed past my eyes, I felt like I had come home.

Beloved showed me a template for an accepting religion at a time where I felt betrayed by the Christianity I had always known. Morrison’s words opened my mind, showing me that there was a home for me in God, if I could only forgive the hurt and exclusion I had felt. Beloved brought me home to my faith and I continue to grow in it, understanding that as long as I can see myself in my faith, there is a home for me.