S1 E1

THURSDAY NEWSLETTER FROM ANDREA BATILLA

VERSACE VERSATILE AND THE MARKETING OF SCARCITY

If we stop talking to someone, even our best friend, sooner or later, we lose them. If we think they’re not a priority, that they’ll always be there waiting for us because they’re loyal, because we’ve known them forever or because we believe they have no alternatives, we lose them. If we think relationships can withstand neglect or absences that feel short but are actually long, we are, consciously or unconsciously, choosing to sever ties. Maybe one day we’ll dial their number and they’ll pick up as if no time has passed. But deep down, we’ll both know that something has broken forever and it cannot be repaired.

Consistency, consideration, listening and attention are everything in any kind of relationship, even when it’s not about emotions but commerce, the exchange of goods and the flow of money.

In the 1980s and ’90s, fashion supported people in their daily lives, meeting their needs whether for an elegant suit, a warm puffer jacket, a well-tailored blazer or a swimsuit. The everyday was an empty space that needed to be filled with objects to make it more luxurious, colorful, soft, or manageable. These objects also represented clear markers of lifestyle, social status, and personal affirmation. It was a system that worked for everyone because no question was left unanswered, not even the most difficult ones.

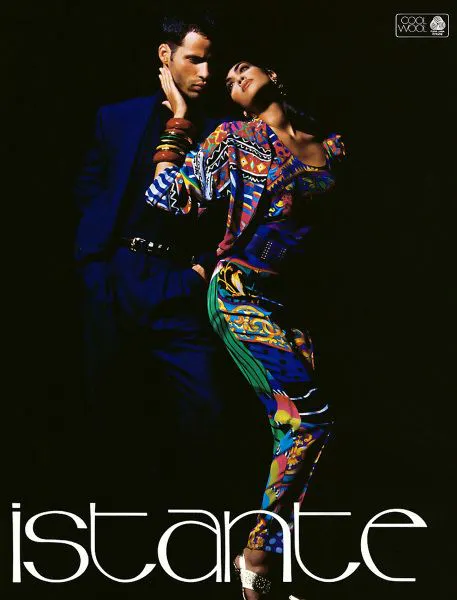

During his career, Gianni Versace, like many of his peers, worked for other brands. Specifically, starting in the 1970s, he designed for Glamur, Florentine Flower, Genny, Byblos, Callaghan, and Complice. By the 1980s, consulting work began to decline, while in-house lines multiplied: Atelier, Couture, Collection, Versus, Versace Jeans Couture, Istante, and the little-known Versatile. The latter collection was created to cater to a market segment that designers found difficult to reach: what were then called plus sizes.

The stretch required from a brand like Versace, which thrived on the cult of the perfect body, to dress women in size XXL was significant. However, at that time, no territory was considered off-limits in fashion. The mindset was about building relationships with all kinds of people, in a way we’d now call inclusive but that was then simply seen as market segmentation. It happened naturally, without the need for intensive merchandising meetings.

Perhaps it’s a hard concept to accept, but one of the reasons for the commercial success of Made in Italy during that era was its accessibility, the extreme availability of its products. In other words, the possibility to buy a Versace piece in some form, even in the local shop of a small provincial town. In a word: the popularization of the brand, without limits and without much reflection. Exactly the opposite of today.

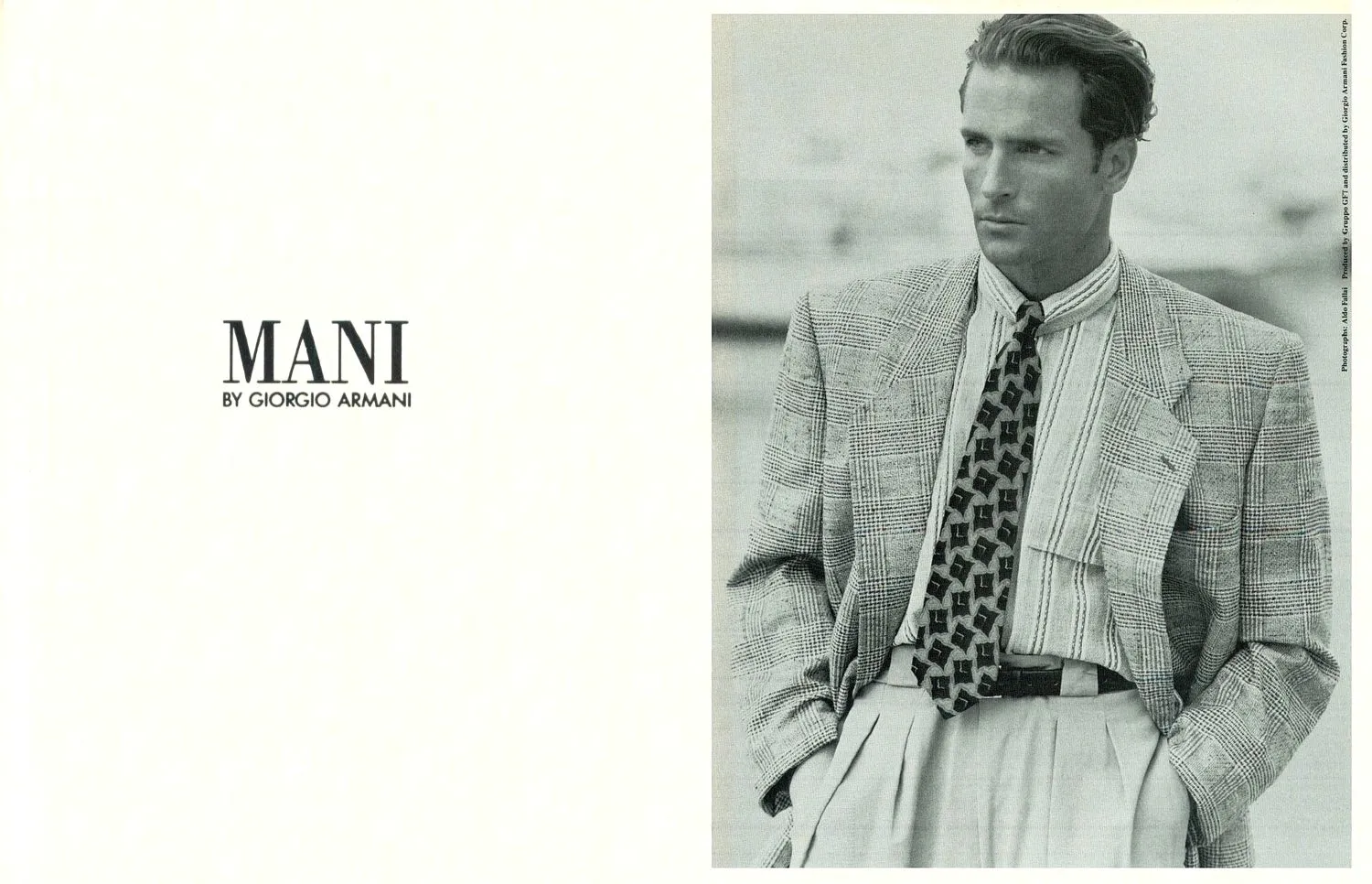

The same applied to Giorgio Armani, who had a second line, called Mani (Italian for hands) or Krizia, who more prosaically named hers Poi by Krizia (literally Then by Krizia) and Ferré with Oaks or even Rhinosaurus Rex which, for those who love historical trivia, was designed by Walter Van Beirendonck. At that time, in an era of consumerism and personality cults, no one feared overexposure in distribution. Everyone looked on with satisfaction as the money from licensees flowed directly into the fashion houses’ bank accounts.

To read the rest of the post you need to subscribe. Through a paid subscription you will help me produce more contents.

SUBSCRIBE (Opens in a new window)

Already a member? Log in (Opens in a new window)