Newsletter No 2 - Samuel Coleridge-Taylor A life of music and colour

Dear Black History Buffs,

This week we are highlighting the contributions of British composer Samuel Coleridge-Taylor.

For those of you who like your history short and snappy, you can check our latest social media posts about him over on Tiktok and Instagram:

For Instagram, click here. (S'ouvre dans une nouvelle fenêtre)

For TikTok, click here. (S'ouvre dans une nouvelle fenêtre)

You can listen to a podcast episode about Coleridge-Taylor if you prefer audio. In the episode, you will get an overview of his life and accomplishments and hear some of his most famous compositions:

For the Podcast, click here. (S'ouvre dans une nouvelle fenêtre)

If you'd like to learn more about his life as a black activist, you can do so using this outstanding google arts & culture link:

For the Google Arts & Culture link, click here. (S'ouvre dans une nouvelle fenêtre)

If you enjoy my content, please share it and this newsletter with your friends and loved ones and consider supporting the creation of more by becoming a member.

The remainder of this newsletter will focus on this one specific question asked by faceless user92630152XXX

It seems a relatively innocent question, right? Well, maybe not; let me explain.

I've been posting historical content on social media for several years now and am used to a particular type of comment from a specific kind of social media user. The pattern is as follows; a goading/sceptical question is asked by a nameless and often faceless user or users with zero posts on their feed. The question is always one they believe is impossible to prove or disprove, and the inquiry aims to derail the post. I'm not saying that is the case in this instance; however, it ticks many boxes. What the poster of this question is really asking is, how can a black man who's never been to Africa be influenced by African music? The further implication is that Coleridge's compositions are solely a product of his European education and environment.

To hammer home, my point below is the very next comment; it's almost as if the same person sent it 🤔

In the past, I would have furiously taken to the comments and duked it out. Lately, I've learned just to let these things slide, but for some reason, these comments really got on my nerves plus, I have time today, so I shall attempt to answer the question.

The TLDR is that Samuel Coleridge Taylor learned about African music the same way we all know about music from other cultures; he listened to it! Duh.

Yea, it's that simple. In 1875 when Coleridge was born, there were Africans in London just living life, and they wrote books, worked jobs, played football and most definitely played music. Multicultural London is not a brand new thing, and Coleridge immersed himself in as much African culture as he could.

A Gold star for anyone who can name the people in the image below:

Now, if you go into the history of Samuel Coleridge Taylor, the African influence on his music is pretty easy to find, but it's all nicely summed up in the article below from Africa: Journal of the International African Institute.

Vol. 57, No. 4, Sierra Leone, 1787-1987 (1987), pp. 566-571 (6 pages)

Published By: Cambridge University Press

The article reads as follows:

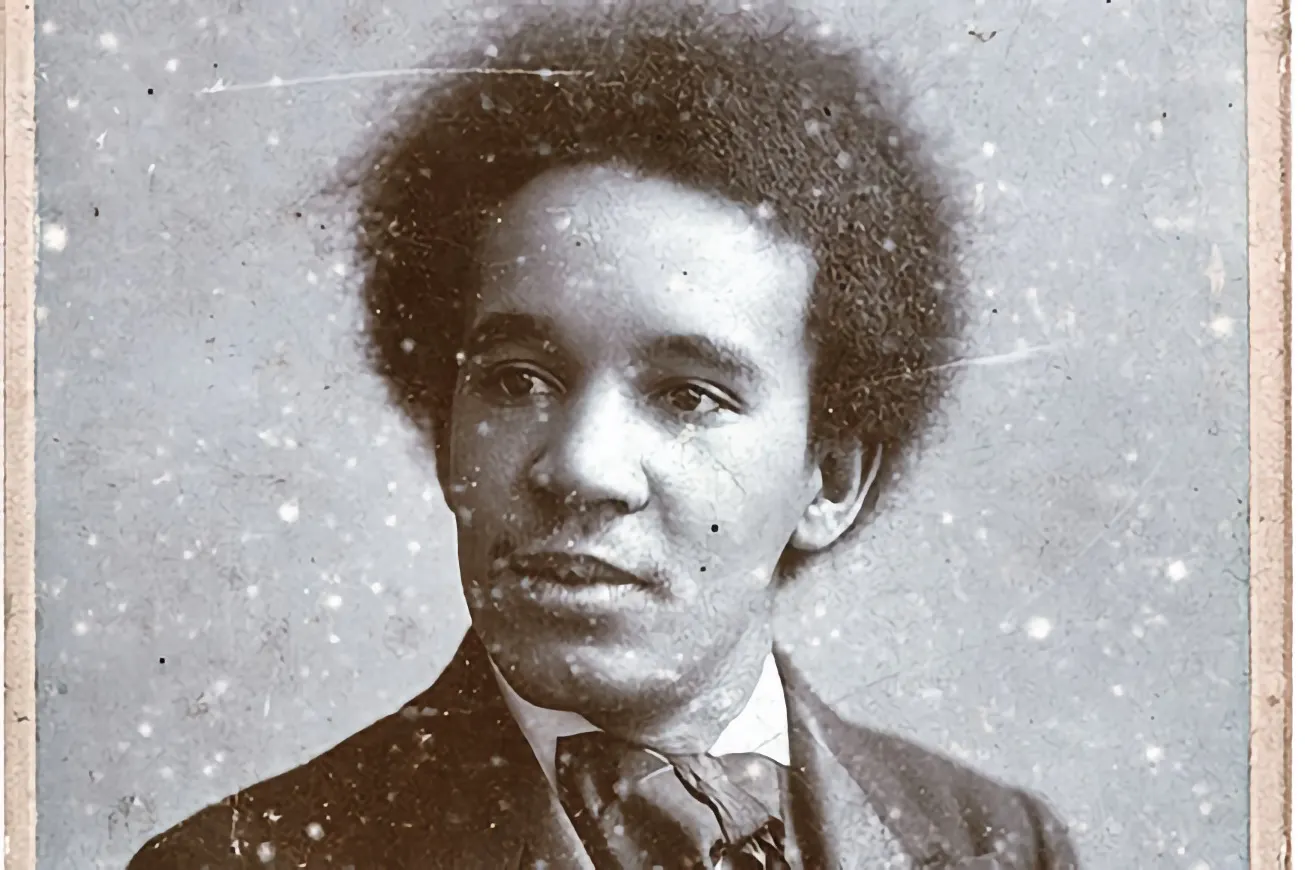

Born in London in 1875, Coleridge-Taylor's father was a Sierra Leonean who came to London to study medicine. Although Coleridge-Taylor never visited Africa, he maintained connections with the West African world through Sierra Leonean friends in London.

His father, D. P. H. Taylor, son of a Freetown trader of Yoruba descent, came to London from Sierra Leone to study medicine at King's College. Qualifying in 1874, he took up a position as assistant to a general practitioner but returned to West Africa in 1879. Most of his subsequent career was spent in private practice in Gambia, and he died in 1904.

Coleridge-Taylor never visited Africa, and connections with his father's birthplace might initially seem tenuous. Sierra Leoneans, however, reckon him as one of their 'sons abroad', a justifiable claim on two counts.

First, Coleridge-Taylor had links with the West African world via Sierra Leonean friends in London.'

Second, he frequently and proudly proclaimed his Africanness through his music. It is this second feature to which the present article draws attention.

Four substantial pieces by Coleridge-Taylor include the word 'African' in their titles: African Romances, seven songs with piano accompaniment to words by the Afro-American poet Paul Dunbar (Op. 17, published 1897), African Suite for piano (Op. 35, published 1899), Four African Dances for violin and piano (Op. 58, published 1904), and Symphonic Variations on an African Air for orchestra (Op. 63, published 1906).

In addition to these four works, several others have explicit African or Afro-American associations. Instances are as follows.

The unaccompanied part song Whispers of Summer and the Five Fairy Ballads (for voice and piano, published 1909) are set to words by a Sierra Leonean friend, Kathleen Easmon.

The plot of the `operatic romance' Dream Lovers (1898), for four soloists and female chorus to words by Paul Dunbar, concerns 'a prince of Madagascar'.

Two orchestral pieces invoke Afro-Caribbean allusions: the concert overture Toussaint l'Ouverture (Op. 46, 1901) and the rhapsody The Bamboula (Op. 75, 1911), based on a dance tune of West Indian origin.

Finally, there are the Twenty-four Negro Melodies for piano (Op. 59), written as an outcome of his first tour of America and published by Oliver Ditson of Boston in 1905. The Twenty-jour Negro Melodies are of special significance in Coleridge-Taylor's output.

Coleridge hoped they would do for black music (both African and Afro-American) 'what Brahms had done for the Hungarian folk music, Dvorak for the Bohemian, and Grieg for the Norwegian'. Coleridge-Taylor saw these pieces as a demonstration of the scope and range of black musicality and, thus, explicitly, as a contribution to the struggle for racial equality.

Coleridge had been particularly inspired by the writings of W. E. B. DuBois and had also visited Booker T. Washington while in the United States. Washington contributed a substantial preface to the Twenry-four Negro Melodies in which he summarised the composer's career and drew attention to the provenance and significance of the folk melodies on which the work was based.'

Coleridge-Taylor's music, therefore, serves as an important contribution to the black history of classical music. Through his compositions, he brought African melodies and rhythms to a broader audience and celebrated his African heritage in a way that was not often seen at the time. He explicitly expressed his version of Africaness in the way he knew best through music. So I hope I answered the question both for the person who answered and for anyone else who might wonder how they can express Africaness having never been to the continent.

This has been a much longer post than originally intended, but I hope you got some value from it. If you did and you'd like to support the creation of more posts like this, please click the link below:

Till next week peace and love,

KK and The Black History Buff team